18 The European Journal of Oriental Medicine

e erapeutic Role of the Practitioner’s

Heart in Classical Chinese Medicine

and Modern Medical Science

A critical literature review

Stéphane Espinosa

Abstract

This critical literature review focuses on the therapeutic role of

the practitioner’s heart, with emphasis on the acupuncturist’s

perspective.

The relevant descriptions given in classical Chinese medicine

are presented. In particular, the appropriate attitude of the

practitioner during treatment is discussed, highlighting the

importance of compassion and clarity of intention. This is followed

by a description of the acupuncture needle’s role of energetic link

with the patient.

Parallels were identified with results from modern research

showing that positive emotions such as compassion increase

the coherence of the cardiac electromagnetic field, and thereby

interpersonal effects such as cardiac energy exchange and

synchronisation of heart rates and heart-brain wave patterns.

The importance of these findings in providing a rationale for a

patient-centred approach to treatment is discussed, together with

the need for further research within the framework of modern

validation of classical Chinese medicine.

Key words

Heart, compassion, intention, spiritual pivot, therapeutic

relationship, acupuncture, energy exchange, biofield,

electromagnetic field, coherence, entrainment, interpersonal

effect, synchronisation.

1. Introduction

The focus of this critical literature review is on the role of the heart

in therapy, with emphasis on the acupuncturist’s perspective, as it

stems from the ancient texts of classical Chinese medicine, as well

as the modern scientific understanding of the heart.

The term ‘classical’ in the title denotes an approach that relies on

tradition and its Daoist roots, in contrast with the more modern

‘traditional Chinese medicine’ whose focus is more pragmatic,

based on scientific materialism and Confucianism (Fruehauf,

2006).

This section presents an overview of this critical literature review

and gives a brief description of the heart from the viewpoints

of classical Chinese medicine and modern medical science

respectively. This section also details the inclusion/exclusion criteria

followed in this review. Section 2 looks at the therapeutic role of

the practitioner’s Heart (心 xin) during treatment, according to

classical Chinese medicine. Section 3 reviews the modern research

on interpersonal physiological and psychological effects of the

heart’s electromagnetic (EM) field, with emphasis on their possible

therapeutic applications. Section 4 is a discussion and reflection

on the information drawn from Sections 2 and 3, in order to

determine the extent to which the knowledge acquired by ancient

Chinese therapists from their practice and intuition is supported

by using the scientific method. Finally Section 5 concludes this

critical literature review.

The Heart (心 xin) has a central importance in classical Chinese

medicine, as discussed in the early acupuncture literature (circa

200 B.C.): the Huang Di Nei Jing (黃帝內經 The Yellow Emperor’s

Classic of Internal Medicine) which is composed of the Su Wen

(素問 Essential Questions) and Ling Shu (靈樞 Spiritual Pivot) (Birch

and Felt, 1999; Lu, 2004; Unschuld, 1985).

In Su Wen chapter 8, which lists the organs, the Heart is in prime

position and is described as the emperor of the whole body (Larre

and Rochat de la Vallée, 1985). This pre-eminent position is due to

the Heart’s relationship with the shen (神), the sacred light which

illuminates the person with the spiritual aspect of the universe

and gives consciousness and discernment (Fruehauf, 2012; Larre

et al, 1986). Shen has also been translated by Maciocia (2005) as

the Mind of a person, and Spirits by Larre and Rochat de la Vallée

(1991b). Ling Shu chapter 71 states the spiritual importance of

the Heart by explaining that it is the residence of the shen (Larre

and Rochat de la Vallée, 1991a; Lu, 2004).

It is important to clarify that in the Chinese language, the

character for the Heart, 心 (xin), refers implicitly to its physical,

but also more importantly to its emotional and spiritual aspects

(Jarrett, 1998; Rochat de la Vallée, 2009; Roth, 1999). Although

it is commonly translated as Heart, xin refers to the core of

the human being. It has no flesh radical (月) which denotes

its immaterial and spiritual aspect. Its physical aspect acts as

a receptacle for the shen (Fruehauf, 2012). Chapter 18 of the

Huainan Zi (淮南子 The Masters/Philosophers of Huainan; written

circa 200 B.C. by Liu An, Prince of Huainan) says that the Heart

The European Journal of Oriental Medicine 19

e erapeutic Role of the Practitioner’s Heart in Classical Chinese Medicine and Modern Medical Science

Stéphane Espinosa

(xin) is that which from a dot extends infinitely (Robinet, 1993).

Xin is both ‘Heart’ and ‘Mind’, inextricably linked as an interactive

unit, so xin may be referred to as the compound ‘Heart-Mind’

(Birch, 2009a; Matsumoto and Birch, 1988). More generally, the

mind, energy, emotion and body are almost never distinguished

in Oriental tradition, but are viewed as a continuum (Matsumoto

and Birch, 1988). This non-dual view of mind and matter is

summarised in the Buddhist Heart Sutra as ‘form is emptiness,

emptiness is form’ (Dalai Lama, 2005: 60).

In Western medicine, until relatively recently the heart was

considered merely as a mechanical pump for blood circulation,

but is now also viewed as a neurological, endocrine and immune

organ, as discussed in detail by Pearsall (1998) and Loh (2008).

The heart’s electrical activity has been studied since the 19th

century, with the electrocardiogram (ECG) first used in 1887

to detect changes in electrical potential on the body surface

(Columbia Encyclopedia, 2012). The natural evolution of this field

of research has been to look at the human EM field (to which

the heart makes the greatest contribution) as part of biofield

physiology research (Hammerschlag, 2012; Hintz et al, 2003;

McCraty, 2003; Rubik 2002, 2005, 2008).

This critical literature review used as inclusion criteria any text (in

English, otherwise French, Spanish or Italian) that is:

• either a translation of a classic Chinese text or a modern

commentary discussing the significance of the Heart in the

Chinese medical model, as it applies to the practitioner, and in

particular to acupuncturists

• a discussion of modern research on interpersonal effects of the

heart’s EM field.

The following exclusion criteria determined the studies beyond the

scope of this review:

• untranslated Chinese texts, even if the abstract is translated

(none appeared in the literature review)

• inner cultivation of the practitioner and possible emission of qi

(for example in medical qigong training) (Chen, 2004; Johnson,

2000)

• discussions on the possible non-local effects of EM elds or

intention (Tiller, 1993)

• ‘limbic resonance’ (tuning into another’s inner emotional state)

(McTaggart, 2011)

• placebo effect (Diebschlag, 2010)

• discussions of heart pathology

• research on the effects of the heart’s EM eld within one person

(McCraty et al, 2009).

2. The therapeutic role of the practitioner’s ‘Heart-Mind’

concept in classical Chinese medicine

The consequences of connecting with the shen are discussed

as early as the Nei Ye (內業 Inward Training; possibly written in

the 5th century B.C., with unclear authorship), which predates

the Su Wen (Birch, 2009a; Roth, 1999): Through self-cultivation

one can refine one’s qi and as a result the shen (the most highly

refined form of qi) resides within the body so one benefits from

shen ming (神明 Divine Illumination) (Puett, 2002). One can then

understand the workings of the universe, and that any change is

the product of qi transformations, thereby obtaining knowledge

about, and control over other things (including humans), since

they all consist of qi (Puett, 2002) . Such a self-cultivated person

can create change without expending energy (Roth, 1999).

In the Zhen Jiu Da Cheng (针灸大成 Great Compendium of

Acupuncture and Moxibustion) compiled in 1601 by Yang

Jizhou (a doctor in the Ming dynasty, 1368-1644) and cited by

Matsumoto and Birch (1988: 38), it says that when the Mind of

the physician has a receptive and accepting attitude, without

desires, it can become shen (神).

Fruehauf (2012) explains that xin (心) is not only a receiver for

the shen, but also a transmitter of this sacred presence from the

immaterial into the material realm, so that shen ming means

making the shen visible in our immediate environment. This can

be interpreted energetically but also through the action of speech.

Indeed, xin governs the tip of the tongue, thereby expressing de

(德 Virtue) with words of wisdom (Fruehauf, 2012). De develops

with self-cultivation and is part of a healer’s training to become a

good practitioner. Besides touch and technique, the Spirit of the

physician is an important consideration in therapy (Matsumoto

and Birch, 1988). In other words, the practitioner may illuminate

the patient with their shen ming energetically as well as with

wise speech.

2.1. Physician attitude

Sun Simiao’s (581-682 A.D.) writings, translated by Unschuld

(1979), advise that during treatment, a great physician has to

be mentally calm and their disposition firm, without wishes or

desires. They have to develop an attitude of compassion and be

willing to make the effort to save every living creature. This echoes

sections 27 and 67 of the Dao De Jing (道德經 The Classic of

the Way and the Virtue; possibly written in the 5th century B.C.

originally by the legendary Lao Zi), which explain that the sage

(who lives according to the Dao) considers their compassion as a

treasure and always helps and rescues living creatures. It would

therefore be beneficial for an acupuncturist to take the sage as

model (Strom, 2004).

When the practitioner’s own Heart is still, trust is established

and contact can be made with the truth in the patient’s Heart.

The healer does not impose their will, but assists patients in

transforming by themselves (Jarrett, 1998). For this to occur, the

appropriate conduct in clinic (and more generally in everyday life)

is obtained by the practice of xin shu (心術 The Art of the Heart)

which cultivates serenity and leads to xin xu (心虚 The Void of the

Heart) where knowledge becomes wisdom (Rochat de la Vallée,

2009).

A different aspect of the practitioner’s appropriate attitude is

described in Su Wen chapter 25 and chapter 54: the hand holding

the needle should be manoeuvred with great concentration and

strength, as if holding a tiger. The acupuncturist should remain

as alert and careful as if being at the edge of an abyss, and they

must rectify their own shen in order to rectify the shen of the

patient (Lu, 2004; Rossi, 2007). This is echoed in Ling Shu chapter

20 The European Journal of Oriental Medicine

9, which explains that while needling, the physician should remain

only attentive to the act of needling, and nothing else, as if being

in a remote place for contemplation (Lu, 2004).

While treating, a practitioner should have a clear intention (by

focusing on the therapeutic function of acupuncture points)

otherwise the effect of their needling will convey an unclear

treatment strategy with unclear results (Yuen, 2005). Clarity of

intention is also brought by alignment with the shen, as discussed

in the following section.

2.2. Spiritual connection with the outside world

Guo Yuzeng (a doctor in the Eastern Han dynasty, 25-220), cited

by Lu (2004: 402) in his translation of the Ling Shu chapter 8, says

that the Spirit is in between the physician’s Heart and their hand.

Thus, acupuncture treatment should be focused on the Spirit,

including the Spirit of the patient and that of the acupuncturist.

The practitioner’s own internal alignment with Heaven (spiritual

development and cultivation of Virtue) is responsible for successful

treatment because it creates a context for healing even before the

needles are inserted (Jarrett, 1998).

During treatment, the practitioner’s ability to use their intention,

the quality of their presence or attention, are as important as the

points selected or the stimulation provided. In other words, the

practitioner may use their qi for further influencing a change in

the patient’s qi (Schnyer et al, 2008).

Furthermore, through the power of their intention, the

practitioner can direct the energies controlled by acupuncture

points. However, the practitioner must understand clearly and

consistently what they intend the points to do if their intention is

to be communicated to the patient’s energy (Pirog, 1996).

Yi (意) refers to intention, without a specific goal or plan for its

realisation, as opposed to thoughts actively translated into

action, which are zhi (志), the Will (Matsumoto and Birch,

1988). With the yi, the practitioner extends their awareness of

the surrounding energy. In addition, their intention and focus

on a selected treatment strategy depend on the clarity of their

connection with the shen (Houghton, 2010). The importance

of this in clinic is that acupuncture points often have several

functions and consequently different effects depending on

the practitioner’s focus and school of thought. In addition,

Gardner-Abbate (1996) describes how a given point function

may have different applications: for example, luo-Connecting

and yuan-Source points of coupled meridians can be used in

combinations or needling styles that are different in the English

or Chinese traditions, to either tonify or disperse the energy of

a meridian (and associated organ), yet clinically those different

strategies work.

The practitioner’s intention is also discussed by Hammer (1990)

who points out the similarity between psychology and Chinese

medicine: the healer is a significant factor in the healing process.

Their intention (both the conscious and the unconscious) and their

life-force are energies capable of profoundly interacting with the

energies of the patient, even influencing them for better or

worse (Hammer, 1990). Lawson-Wood (1973) cited by Hammer

(1990) also states that the practitioner’s Mind, their intention,

has great influence upon the quality of the treatment that they

will administer.

Hammer (1990) stresses the fact that the physician remains

objective in their diagnosis, in particular via the art of observation

of phenomena, but not alienated (such as Western physicians may

be due to the lack of training of their senses and a cultural bias

in favour of ‘professional distance’). Together with needles and

herbs, their energy is accepted as a meaningful part of the healing

process. In particular, when the practitioner lays hands on the

patient, in terms of healing, there is the transmission of the sense

of caring, which is a form of love. Love is ultimately the great

healer, and in such a relationship the physician and patient are

mutually nourished (Hammer, 1990).

Finally, Fruehauf (2012) gives a poetic description of xin as being

a central altar with the functions of connecting with the shen, but

also establishing and maintaining unity (through the act

of connection of the micro and macrocosms) and community

(by connection to a higher nature).

2.3. Spiritual pivot

Birch (2009a) reviewed the translations of Ling Shu chapter 1,

where it is said that the shen or the Mind (the Heart being of

course the link between the two translations) of the practitioner

should focus at the needle tip for effective needling, which implies

an effect of the Mind on the qi.

In their commentary of Ling Shu chapter 8, Larre and Rochat de

la Vallée (1991b) explain that the needle can be like a pivot that

establishes communication so that the influences of Heaven (the

spiritual aspect of life) can penetrate the patient. The Spirits, shen,

are like messengers, carrying the influence of Heaven, so they

are an intermediary between Heaven and Man, and the centre

of reception of these influences is the void of xin, the Heart-

Mind. Firebrace (1993), cited by Blackwell et al (1993), says that

the practitioner should have good shen ming (Radiance of the

Spirit), as a catalyst in treatment (and for their own preservation),

although the acupuncture treatment works of itself, using the

needle as a ‘ling shu’, a Spiritual Pivot. Larre and Rochat de la

Vallée (1991b) then suggest that the shen can pass between

the physician and the patient, or the physician himself is just

a pivot like the needle to re-establish an equilibrium that has

been disturbed.

The Zhen Jiu Da Cheng (mentioned above), cited by Matsumoto

and Birch (1988: 38), explains that the xin of the physician and the

patient should be level and in harmony, following the movements

of the needle. Consequently, the acupuncturist, patient and needle

form a synergetic unit so that the healing process goes beyond the

mere fact of needling (White et al, 2008). Indeed, for an effective

treatment, the acupuncturist goes all the way to the origin of the

patient’s life, to the place where the Spirits are rooted in order to

attract them so that they bring forth the Heavenly influence in the

patient (Larre and Rochat de la Vallée, 1992, 1995).

The European Journal of Oriental Medicine 21

3. Review of research on interpersonal effects of the human

heart EM field

3.1. Cardiac energy exchange

The heart generates the strongest EM field of the body (up to

100 times stronger than that produced by the brain) and can

be measured meters away from the body (McCraty et al, 1998;

McCraty et al, 2012). Pearsall (1998) concurs by stating that when

the heart beats, it generates energy that is not contained within

us, and thereby may be able to signal other hearts. Moreover,

cellular regulation can be influenced by EM fields pulsing in the

same frequency range as the cardiac field, hence it is possible that

a practitioner’s heart has a therapeutic effect by influencing the

patient via its radiated EM field (Oschman, 2003).

This is of particular relevance because the lack of a plausible

mechanism to explain the nature of an energy exchange between

people, or how it could affect or facilitate the healing process,

causes a major block for its acceptance by Western science

(McCraty et al, 1998). Consequently, the possibility of people

exchanging energy via the heart EM field was investigated by

Russek and Schwartz (1994) as well as McCraty et al (1998).

The first step was to consider how an external EM field may

affect biological systems, given that the EM field radiated by

the human heart was theoretically calculated to be too weak

(Weaver and Astumian, 1990). The proposed underlying

mechanisms were cellular signal averaging (where the cell’s

membrane averages the EM field, which reduces the noise –

random fluctuating thermal energy) and stochastic resonance

(where the noise within a biological system is entrained by an

external periodic signal – here the cardiac EM wave – thereby

increasing the signal intensity up to a level where it can interact

with the system) (McCraty, 2003).

Both groups independently demonstrated that when people

touch or are in proximity, the ECG signal of one person (the

‘source’) is registered in another person (the ‘receiver’) on the

body surface (including in the electroencephalogram (EEG)), hence

showing an exchange of EM energy produced by the human

heart (McTaggart, 2008). This occurred in both directions (the two

persons affecting each other: the other’s ECG signal detected in

one’s EEG) in about 30 per cent of the subject pairs, otherwise

only in one direction, indicating a varying degree of signal

transmission. Indeed, Russek and Schwartz (1994) determined

that people more accustomed to receiving love and care appear

to be better receivers of others’ cardiac signals, and therefore

this energy exchange plays an important role in empathy and

sensitivity to others (McCraty, 2003).

In addition, when a person feels a positive emotion (such as

sincere love or appreciation) or has a caring intention, this

increases coherence (the periodic nature) in the cardiac rhythm

(and hence in the EM field), providing various health benefits,

such as higher immunity, reduced hypertension or emotional

disorders; by contrast, a negative emotion is associated with a

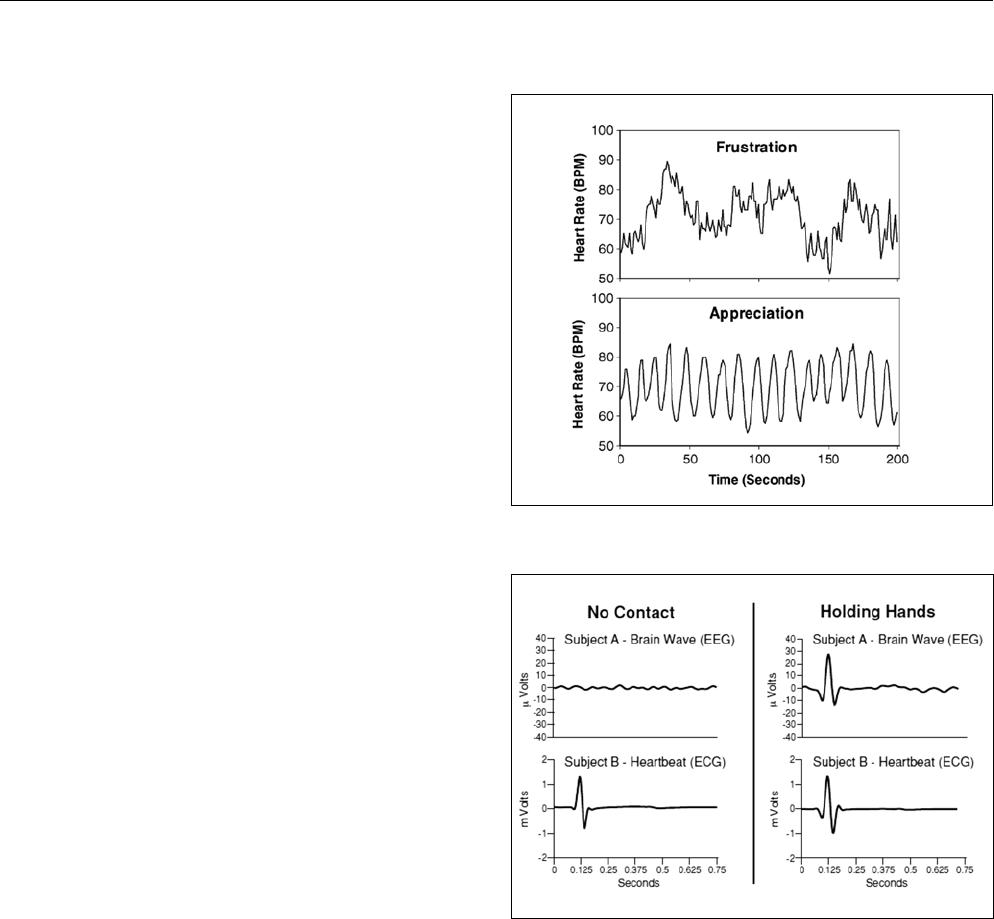

more erratic pattern, as shown in figure 1 (McCraty et al, 2009;

Rosch, 2009; Tiller, 1990).

Figure 1: Emotions are reflected in heart rhythm patterns

(McCraty et al, 2009: 22).

Figure 2: The electricity of touch, heartbeat signal averaged

waveforms

(McCraty, 2003: 9)

In other words, in these circumstances clearer information is being

transmitted outside of the body. This prompted McCraty et al

(1998) to propose that via the mechanism of stochastic resonance,

this increased coherence may improve the cardiac energy

exchange between people. In particular, the nervous system may

act as an antenna, responding to the EM fields produced by the

hearts of other people (McCraty, 2003; McCraty et al, 2005).

In their experiments, McCraty et al (1998) did not instruct their

subjects to have any specific intention or feeling state (presumably in

order to introduce fewer variables in the initial study). The transfer of

cardiac energy was detected when the subjects were holding hands

(or in close proximity – about 45cm) as shown on the right side of

figure 2, but not when separated by one meter (figure 2 left side). In

figure 2, the source and receiver are subjects B and A, respectively (no

difference was found between genders) (McCraty, 2003).

e erapeutic Role of the Practitioner’s Heart in Classical Chinese Medicine and Modern Medical Science

Stéphane Espinosa

22 The European Journal of Oriental Medicine

However, Russek and Schwartz (1994) did observe in their

preliminary results the energy exchange between people (heart-

brain and heart-heart) for a distance between subjects of up to

one meter, with their eyes closed and not communicating in any

tactile, visual, or auditory way. This discrepancy in detections is

possibly due to the reasons stated above (variability of source

and receiver) as well as duration of observation time (affecting

the averaging of the signal and thereby the noise level). Finally,

by comparing the amplitude of the transferred signal observed in

hand holding and non-contact trials (tenfold amplitude reduction

in the latter type, with distance taken into account), McCraty et

al (1998) concluded that electrical conduction (through direct skin

contact) plays a bigger role than EM radiation. (For completeness,

McCraty (2003) mentioned that instead of a radiated wave, the

signal may be transferred by electrical capacitive coupling due

to the potential difference between individuals). In any case,

this observed cardiac energy exchange represents a plausible

mechanism for how one person can sense the presence of

another and even their emotional state, independent of other

signals such as body language (McCraty et al, 2009).

Morris (2010) then researched ‘collective coherence’, that is

whether a group of people trained in achieving a high state

of coherent cardiac field (focusing on the heart rate variability)

could facilitate coherence in an untrained person. Using 15

trained ‘senders’ and as many non-trained ‘receivers’, the study

comprised a series of 148 10-minute trials. Each session consisted

of a receiver seated in close proximity to three senders who were

instructed to alternatively direct toward the receiver their focused

care and compassion, or focus on their coherence technique with

no attention directed to the receiver.

Due to the wide variability in the receivers’ achieved coherence,

significant differences were difficult to establish, so a matched

comparison analysis was conducted, showing that receivers

obtained a higher coherence in 47.3 per cent of the cases.

Another result was that when senders focused on achieving

high coherence themselves, it better helped in raising the

receiver’s coherence than when attempting to facilitate the

process. Morris (2010) interpreted this finding as indicating that

the act of trying to direct facilitative energy may actually interfere

with energetic transfers.

Morris (2010) then explained that the study design had assumed

that senders could influence the receiver’s cardiac field unilaterally.

However, the sender-receiver circuit appears in fact to be a

dynamic two-way channel, possibly influenced by either party. By

asking participants how they felt about each other, Morris (2010)

determined that the quality and extent of their interpersonal

relationships had a greater effect on any energetic interaction,

than the actions and intentions of the senders.

3.2. Interpersonal heart-brain synchronisation

In further non-contact trials, McCraty (2003) separated the

subjects by one and a half meters and asked them to maintain a

positive emotional state (although no specific intention to send

energy) in order to produce a sustained coherent cardiac EM field.

McCraty (2003) showed that the receiver’s alpha waves rhythm

(one type of the brain’s oscillating electrical voltages) synchronised

with the source’s ECG pattern, but only if the receiver maintained

a coherent field, which could be the reason for being more

sensitive to others’ cardiac signals, as discussed above (Russek

and Schwartz, 1994; Tiller, 1990). McCraty (2003) highlighted

the importance of this interpersonal non-contact heart-brain

synchronisation, as it may play a role in the non-verbal aspect

of therapeutic interactions (by promoting greater rapport and

empathy). However, he did not elaborate on the significance

of the synchronisation occurring with this particular type of

brain wave. Oschman (2000) also conjectured that the source’s

radiated EM field may have healing power thanks to its ability

to entrain (synchronise) similar coherent rhythms in the tissues

of the receiver.

The results by McCraty (2003), McCraty et al (1998) and Russek

and Schwartz (1994) reported in sections 3.1 and 3.2 were from

selected representative examples to be considered as a proof of

concept rather than be subjected to statistical analysis. There

was no discussion of the level of blinding selected and whether

randomization was used.

3.3. Interpersonal heart-heart synchronisation

McCraty (2003) also reported anecdotal evidence of heart rhythm

entrainment (synchronisation) between individuals having a close

relationship and while they focused on generating feelings of

appreciation for each other. Subjects were separated by about one

meter. Intermittent heart rate synchronisation was also observed

during sleep in couples who are in long-term stable and loving

relationships (McCraty 2003).

Subsequently and independently, Bair (2006, 2008) conducted

research on the heart rate synchronization between a healer

having a positive intent and a subject. The total sample size

was 91 adults, of which 41 comprised the control group. All

participants came for a one-hour treatment and during the

session were taught how to apply a self-relaxation technique,

while being kept blind to the study’s actual focus. Pulse and

respiration were checked before and after the session. The healer

was presented as a researcher and met the whole control group

together for one hour, remained more than six meters away from

participants and without specific intention. The healer then met

individual members of the intervention population for one hour,

and sat within one and a half meters of the participant (distance

determined from McCraty’s (2003) results), focusing on a heart

connection of compassion and highest good.

Bair (2006) found that the healer effect was visible in the

synchronisation of healer/subject heart rates in the intervention

subjects (which did not occur in the control subjects). Whereas

before the session there was no significant correlation, just after

the treatment 60 per cent of the intervention population had

heart rates within ±2 beats per minute of the healer’s. Pearson’s r

analysis (a measure of correlation) on the healer and subject heart

The European Journal of Oriental Medicine 23

rates was .671 (P ≤.001 hence statistically significant) indicating a

strong correlation. The healer effect was also apparent in a higher

degree of reported (hence subjective) health improvements in the

intervention population (reduced level of distress concerning the

issue for which they had the treatment).

Bair (2008) explained that heart rate synchronisation implies

a resonance entrainment (made possible due to the healer’s

cardiac EM field being coherent), with the possibility of transfer

of information or regulation between healer and subject

(corroborated by the reported health improvement), although it

may occur on an energy level below the threshold of conscious

awareness.

Morris (2010) also observed heart rate synchronisation between

participants in his ‘collective coherence’ study (section 3.1), with

870 inter-subject heart rate observations in total. Of the subject

pairs, 37.9 per cent showed a correlation statistically significant

from zero (Pearson’s r > .062 at P ≤.05, given the large number

of data: 2400 samples in a ten-minute time series). Interestingly,

higher levels of heart rate synchronisation were found to be

correlated with higher coherence levels (of heart rate variability).

4. Discussion

Schnyer et al (2008) suggested that there is a form of

physiological concordance in the patient-practitioner interaction.

They proposed that there is a relationship between simultaneous

changes in physiological measures (such as heart rate, skin

conductance, blood pressure, respiratory rate, etc.) between

the patient and practitioner, which enables access to the

signalling system activated by acupuncture. They also stated that

experimental evidence is not yet present.

However, in view of section 3, modern research has started

providing such evidence. McCraty (2003) explained that a clinician

with heartfelt positive emotions and attitudes will have a more

coherent cardiac field (to which the patient is exposed), which

may enhance the non-verbal aspect of the therapeutic interaction,

and possibly also positively affect the patient’s physiology and

receptivity to treatment. This last statement has started to be

researched by Bair (2006), who reported results of reduced

levels of distress (see section 3.3), implying that more than just

synchronization is happening.

Also, as Birch (2009b) pointed out, since an acupuncture

treatment involves touch of the patient by the practitioner, the

cardiac energy exchange does occur and may trigger changes in

the patient’s EM field (via the EM fields of the heart and brain).

The effect would be to induce or enhance beneficial physiological

effects produced by an increase in the patient’s cardiac field

coherence. This modern view of linkage by a coherent cardiac

field parallels the 17th century recommendation given in the Zhen

Jiu Da Cheng (mentioned in section 2.3), cited by Matsumoto and

Birch (1988: 38), that the xin (the Heart-Mind) of the physician

and the patient should be level and in harmony, following the

movements of the needle.

Interestingly, the needles used in acupuncture are metallic, and

as such they conduct electricity while being affected by the

surrounding EM field. When a needle is inserted at the location of

an acupuncture point, it will affect the electrical current flowing in

the corresponding meridian (Becker and Selden, 1985). Hence the

effect of the practitioner’s coherent cardiac field on the patient

may be focused by the needle. This idea resonates with the

concept of ‘ling shu’ (detailed in section 2.3), the Pivot passing

the shen between practitioner and patient.

In both classical Chinese and modern approaches, the

practitioner’s intention or mental focus is an important

factor modulating the effect of the heart. Indeed, a healer’s

compassionate intent can cause interpersonal non-contact

synchronisation of heart and brain, as shown by McCraty (2003)

(section 3.2), as well as heart rates (Bair 2006) (section 3.3).

Morris (2010) also observed heart rate synchronisation in his

‘collective coherence’ study (section 3.1), opening up the

possibility for what he calls ‘heart-to-heart bio-communications’

(Morris 2010: 72). Therefore practising emotional empathy

is mutually beneficial, as thoughts and emotions are likely to

influence the qualitative aspects of the energetic interactions

between people. This is consistent with Pearsall (1998) who

proposes that a patient is healed by the presence of ‘healing

loving hearts’ joining with their heart, and not just by the actions

of medical staff. However, Morris (2010) explained that, based on

his results, it is best not to try to impose a particular emotional

state on others, as energetic interactions seem to be impeded

rather than enhanced when over-engaging the mind relative to

the heart. In other words, personal coherence seems to be the

best foundation to forge collective coherence. This is supported by

the results of a large-scale sociological project (5,124 participants)

using data of the Framingham Heart Study: a happy next-door

neighbour increases one’s probability of happiness by 34 per

cent, and a happy friend living within a mile by 25 per cent

(this effect decays with time and geographical separation). This

implies that happiness, like health, should be seen as a collective

phenomenon, since people’s happiness depends on the happiness

of others with whom they are connected (Fowler and Christakis,

2008; McTaggart, 2011).

5. Conclusion

The recent research findings from McCraty et al (1998, 2005,

2009), Russek and Schwartz (1994), Bair (2006) and Morris (2010)

indicate that the practitioner’s heart plays a role in the healing

encounter. In particular, the observed cardiac energy exchange

and interpersonal synchronisation parallel the classical Chinese

medical descriptions of the physician’s appropriate behaviour

and the acupuncture needle acting as a link and focus of energy

passing to the patient. These preliminary results warrant further

research: a comprehensive rigorous study of these elements of

convergence, which may provide a basis for further modern

validation of classical Chinese medicine, and thereby a greater

public acceptance.

e erapeutic Role of the Practitioner’s Heart in Classical Chinese Medicine and Modern Medical Science

Stéphane Espinosa

24 The European Journal of Oriental Medicine

This research should eventually benefit the patients’ health, hence

the increasing interest on this topic, with gradually more Western

doctors asking whether the subtle bioelectromagnetic energy can

be harnessed for health enhancement (Rosch 2009). The results

reported in this review already show the importance of a patient-

centred rather than a disease-centred approach to treatment

(Jones 2010). In other words, Western-trained clinicians should

evolve from the role of ‘curing disease through modern science’

and back to their traditional role of ‘healer of the sick’, forming a

‘healing partnership’ with the patient (Jones et al, 2010: 72).

This has started to be considered carefully, for example by Miller

et al (2009) who characterized the placebo effect as a form of

interpersonal healing, instead of being an umbrella term for every

non-understood effect (such as EM field, beliefs or relationships)

(Diebschlag, 1993). Hence the cultivation of the practitioner’s

intention has important implications for treatment, as it enhances

both clarity of intention and the capacity to maintain energetic

coherence despite the patient’s influence (Diebschlag, 2010).

Finally, during an acupuncture treatment, the therapeutic

relationship has both specific and non-specific aspects. Rapport

building with compassion (increasing cardiac coherence) and

communication to engender empathy might be seen as non-

specific. Yet at least the two following aspects are specific to

acupuncture: 1. The fact that the needle acts as a pivot to focus

the practitioner’s intention; 2. Palpatory diagnosis to identify

points may have a therapeutically active component (MacPherson

et al, 2006; Schnyer et al, 2008; White et al, 2008). Both aspects

are consistent with the observations of cardiac energy transfer

being greater when people are in direct contact and highlight

the therapeutic role of the practitioner’s heart.

Acknowledgements

This article formed part of a BSc project for the International

College of Oriental Medicine, validated by the University of

Greenwich. Special thanks go to Francesca Diebschlag for her

thoughtful comments.

References

Bair, C. C. (2006). The heart field effect: Synchronization of healer-subject

heart rates in energy therapy Holos University (online) last accessed

02.03.2013 at http://holosuniversity.net/pdf/bairDissertation.pdf

Bair, C. C. (2008). The heart field effect: Synchronization of healer-subject

heart rates in energy therapy. Advances In Mind-Body Medicine, 23 (4),

10-19.

Becker, R. O. and Selden, G. (1985). The Body Electric: Electromagnetism

and the Foundation of Life. New York: Harper.

Birch, S. (2009). Filling the Whole in Acupuncture Part 1:1 What are we

doing in the supplementation needle technique? European Journal of

Oriental Medicine, 6 (2), 25-35.

Birch, S. (2009b). Filling the Whole in Acupuncture Part 1:2 What are we

doing in the supplementation needle technique? Scientific perspectives.

The European Journal of Oriental Medicine, 6 (3), 18-27.

Birch, S. and Felt, R. (1999). Understanding Acupuncture. London:

Churchill Livingstone.

Blackwell, R., De Soriano, G., Firebrace, P., Royds, R., Rusher, R. and

Uddin, J. (1993). The Spirit: Some Practitioner Viewpoints. The European

Journal of Oriental Medicine, 1 (1), 19-24.

Chen, K. W. (2004). An Analytic Review of Studies on Measuring Effects of

External Qi in China. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine, 10 (4),

38-50 (online) last accessed 02.03.2013 at http://qigonginstitute.org/html/

Chen/Waiqianalysis_0704.pdf

Columbia Encyclopedia (2012) Electrocardiography in The Columbia

Electronic Encyclopedia 6th edition, Columbia University Press (online) last

accessed 02.03.2013 at http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1E1-electroca.

html

Dalai Lama. (2005). Essence of the Heart Sutra: The Dalai Lama’s Heart of

Wisdom Teachings. US: Wisdom Publications.

Diebschlag, F. (1993). Placebo Acupuncture. University of Exeter.

Diebschlag, F. (2010). The Therapeutic Relationship: A Workbook for the

Healing Professions. Francesca Diebschlag (Standard Copyright Licence).

Fowler, J. H. and Christakis, N. A. (2008). Dynamic spread of happiness

in a large social network: longitudinal analysis over 20 years in the

Framingham Heart Study. British Medical Journal, 337, a2338 (online) last

accessed 02.03.2013 at http://www.readcube.com/articles/10.1136/bmj.

a2338

Fruehauf, H. (2006). Classical Chinese Medicine vs Traditional Chinese

Medicine. Holisticwebs.com (online) last accessed 02.03.2013 at http://

www.qiwithoutborders.org/classical-TCM.html

Fruehauf, H. (2012). The Organ Networks of Chinese Medicine: Heart.

Classical Chinese Medicine organisation (online) last accessed 02.03.2013

at http://www.classicalchinesemedicine.org/af/av/cosmo/organ-networks-

heart/

Gardner-Abbate, S. (1996). Holding the Tiger’s Tail: An acupuncture

techniques manual in the treatment of disease. Santa Fe: Southwest

Acupuncture College Press.

Hammer, L. I. (1990). Dragon Rises, Red Bird Flies: Psychology and

Chinese Medicine. The Aquarian Press.

Hammerschlag, R. (2012). Biofield Physiology: Exploring Interfaces

between Biofield Healing and Conventional Physiology. 14th Annual

Research Symposium. Acupuncture Research Resource Centre (online)

last accessed 02.03.2013 at http://arrcsymposium.org.uk/dr-richard-

hammerschlag-biofield-physiology-exploring-interfaces-between-biofield-

healing-and-conventional-physiology.html

Hintz, K. J., Yount, G. L., Kadar, I., Schwartz, G., Hammerschlag,

R. and Lin, S. (2003). BioEnergy Definitions and Research Guidelines.

Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine 9 (3), 13-30 (online) last

accessed 02.03.2013 at http://mindbodylab.bio.uci.edu/publications/

Bio%20Def%20and%20Research%20Guidelines.pdf

Houghton, J. (2010). To elucidate the role of Yi Shi 意識 within the

practice of Acupuncture. International College of Oriental Medicine.

Jarrett, L. S. (1998). Nourishing Destiny, the Inner Tradition of Chinese

Medicine. Massachusetts, USA: Spirit Path Press.

Johnson, J. A. (2000). Chinese Medical Qigong Therapy: A

Comprehensive Clinical Text. The International Institute of Medical

Qigong.

Jones, D. S. (2010). Needed: A coherent architecture for 21st century

clinical practice and medical education. Alternative Therapies in Health

and Medicine, 16 (4), 64-67 (online) last accessed 02.03.2013 at http://

www.heartmath.org/templates/ihm/downloads/pdf/research/publications/

coherent-architecture-for-21st-century.pdf

Jones, D. S., Hofmann, L. and Quinn, S. (2010). 21st Century

Medicine: A New Model for Medical Education and Practice. The Institute

for Functional Medicine (online) last accessed 02.03.2013 at http://www.

functionalmedicine.org/listing_detail.aspx?id=2337&cid=0

Larre, C. and Rochat de la Vallée, E. (1985). Huang Di Nei Jing Su Wen

Chapter 8: The Secret Treatise of the Spiritual Orchid. British Register of

Oriental Medicine.

The European Journal of Oriental Medicine 25

Larre, C. and Rochat de la Vallée, E. (1991a). Aspects of the Heart.

Review of Oriental Medicine 9, 6-9.

Larre, C. and Rochat de la Vallée, E. (1991b). The Heart in Lingshu

Chapter 8. London: Monkey Press.

Larre, C. and Rochat de la Vallée, E. (1992). Les mouvements du coeur:

Psychologie des Chinois. Paris: Desclée de Brouwer.

Larre, C. and Rochat de la Vallée, E. (1995). Rooted in Spirit: The Heart

of Chinese Medicine. New York: Station Hill Press.

Larre, C., Schatz, J. and Rochat de la Vallée, E. (1986). Survey of

Traditional Chinese Medicine. Paris: Institut Ricci.

Loh, R. (2008). Views of the Heart: Parallels and divergences between

Chinese and Western perspectives of the heart. A literature review.

International College of Oriental Medicine.

Lu, H. C. (Trans.) (2004). A Complete Translation of the Yellow Emperor’s

Classics of Internal Medicine and the Difficult Classic (Nei-Jing and Nan-

Jing). International College of Traditional Chinese Medicine of Vancouver.

Maciocia, G. (2005). The Foundations of Chinese Medicine, A

Comprehensive Text for Acupuncturists and Herbalists 2nd edition.

Edinburgh: Elsevier.

Matsumoto, K. and Birch, S. (1988). Hara Diagnosis: Reflections on the

Sea. Massachusetts, USA: Paradigm Publications.

MacPherson, H., Thorpe, L. and Thomas, K. (2006). Beyond

Needling – Therapeutic Processes in Acupuncture Care: A Qualitative

Study Nested Within a Low-Back Pain Trial. The Journal of Alternative

and Complementary Medicine, 12 (9), 873-880 (online) last accessed

02.03.2013 at http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail?vid=5&sid=ff8007ca-

2744-4335-a7b8-9187df46df1c%40sessionmgr13&hid=28&bdata=JnNpd

GU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#db=aph&AN=23122026

McCraty, R. (2003). The Energetic Heart, Bioelectromagnetic Interactions

Within and Between People. Institute of HeartMath.

McCraty, R., Atkinson, M., Tomasino, D. and Tiller, W. A. (1998).

The Electricity of Touch: Detection and measurement of cardiac energy

exchange between people in Pribram, K. H. (ed.). Brain and Values: Is

a Biological Science of Values Possible Lawrence. Erlbaum Associates

Publishers (online) last accessed 02.03.2013 at http://www.heartmath.org/

research/research-publications/electricity-of-touch.html

McCraty. R., Atkinson, M., Tomasino, D. and Bradley, R. T. (2009). The

Coherent Heart: Heart–Brain Interactions, Psychophysiological Coherence,

and the Emergence of System-Wide Order. Integral Review 5 (2), 10-115

(online) last accessed 02.03.2013 at http://integral-review.org/back_issues/

backissue9/index.asp

McCraty, R., Bradley, R. T. and Tomasino, D. (2005). The Resonant

Heart. Shift: At the Frontiers of Consciousness 5, 15-19 (online) last

accessed 02.03.2013 at http://noetic.org/library/magazines/shift-issue-5/2/

McCraty, R., Deyhle, A. and Childre, D. (2012). The Global Coherence

Initiative: Creating a Coherent Planetary Standing Wave. Global Advances

in Health and Medicine, 1 (1), 64-77 (online) last accessed 02.03.2013 at

http://www.heartmath.org/research/research-publications/gci-creating-a-

coherent-planetary-standing-wave.html

McTaggart, L. (2008). The Intention Experiment: Use Your Thoughts to

Change the World. London: Harper Element.

McTaggart, L. (2011). The Bond: Connecting through the space between

us. Hay House UK.

Miller, F. G., Colloca, L. and Kaptchuk, T. J. (2009). The Placebo Effect,

illness and interpersonal healing. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 52

(4), 518-39 (online) last accessed 02.03.2013 at http://tedkaptchuk.com/

selected-publications

Morris, S. M. (2010). Achieving collective coherence: Group effects

on heart rate variability coherence and heart rhythm synchronization.

Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine, 16 (4), 62-72 (online)

last accessed 02.03.2013 at http://www.heartmath.org/templates/ihm/

downloads/pdf/research/publications/achieving-collective-coherence.pdf

Oschman, J. L. (2000). Energy Medicine: The Scientific Basis. Elsevier.

Oschman, J. L. (2003). Energy Medicine in Therapeutics and Human

Performance. Elsevier.

Pearsall, P. (1998). The Heart’s Code: Tapping the Wisdom and Power of

Our Heart Energy. New York: Broadway Books.

Pirog, J. E. (1996). The Practical Application of Meridian Style

Acupuncture. California, USA: Pacific View Press.

Puett, M. J. (2002). To Become a God: Cosmology, Sacrifice, and Self-

Divinization in Early China. Massachusetts, USA: Harvard University Press.

Robinet, I. (Trans.) (1993). Traduction du dix-huitieme chapitre: Parmis

les hommes in Larre, C., Robinet, I. and Rochat de la Vallée, E. (eds.). Les

grands traits du Huainan zi. Paris: Les Editions du Cerf.

Rochat de la Vallée, E. (2009). Les 101 Notions-Clés de la Médecine

Chinoise, 2nd edition. Paris: Guy Trédaniel Editeur.

Rosch, P. J. (2009). Bioelectromagnetic and Subtle Energy Medicine: The

Interface between Mind and Matter. Annals of the New York Academy of

Sciences, 1172, 297-311 (online) last accessed 02.03.2013 at http://www.

methodesurrender.fr/docs/art_bsem_2009.pdf

Rossi, E. (2007). Shen: Psycho-Emotional Aspects of Chinese Medicine.

Edinburgh: Elsevier.

Roth, H. D. (1999). Original Tao: Inward Training (Nei Yeh) and the

Foundations of Taoist Mysticism. New York: Columbia University Press.

Rubik, B. (2002). The Biofield Hypothesis: Its Biophysical Basis and Role in

Medicine. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 8 (6),

703-717 (online) last accessed 02.03.2013 at http://web.ebscohost.com/

ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=06fa9a55-b62e-4a20-ba42-95adfff4ed33

%40sessionmgr115&vid=2&hid=105

Rubik, B. (2005). The Flame of Life. Shift: At the Frontiers of

Consciousness, 5, 20-24 (online) last accessed 02.03.2013 at http://noetic.

org/library/magazines/shift-issue-5/3/

Rubik, B. (2008). Measurement of the Human Biofield and Other Energetic

Instruments in Freeman, L. (ed) Mosby’s Complementary & Alternative

Medicine: A Research-Based Approach: A Research-based Approach.

Mosby Elsevier (online) last accessed 02.03.2013 at http://www.faim.org/

energymedicine/measurement-human-biofield.html

Russek, L. G. and Schwartz, G. E. (1994). Interpersonal Heart-Brain

Registration and the Perception of Parental Love: A 42 Year Follow-Up of

the Harvard Mastery of Stress Study. Subtle Energies, 5 (3), 195-208.

Schnyer, R. N., Birch, S. and MacPherson, H. (2008). Acupuncture

practice as the foundation for clinical evaluation in MacPherson, H.,

Hammerschlag, R., Lewith, G. and Schnyer, R. N. (eds.) Acupuncture

Research, Strategies for Establishing an Evidence Base. Edinburgh: Elsevier.

Strom, H. (Trans.) (2004). Livre de la Voie et de la Vertu: Laozi – Dao De

Jing à l’usage des acupuncteurs. Paris: Edition You Feng.

Tiller, W. A. (1990). A Gas Discharge Device for Investigating Focussed

Human Attention. Journal of Scientific Exploration, 4 (2), 255-271 (online)

last accessed 02.03.2013 at http://www.scientificexploration.org/journal/

jse_04_2_tiller.pdf

Tiller, W. A. (1993). What are subtle energies? Journal of Scientific

Exploration, 7 (3), 293-304 (online) last accessed 02.03.2013 at http://

www.scientificexploration.org/journal/jse_07_3_tiller.pdf

Unschuld, P. U. (1979). Medical Ethics in Imperial China: A Study in

Historical Anthropology. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Unschuld, P. U. (1985). Medicine in China: A History of Ideas. Berkeley:

University of California Press.

Weaver, J. C. and Astumian, R. D. (1990). The response of living cells

to very weak electric fields: The thermal noise limit. Science, 247, 459-

462 (online) last accessed 02.03.2013 at http://www.highbeam.com/

doc/1G1-8533713.html

White, P., Linde, K. and Schnyer, R. N. (2008). Investigating the

components of acupuncture treatment in MacPherson, H., Hammerschlag,

R., Lewith, G. and Schnyer, R. N. (eds.) Acupuncture Research, Strategies

for Establishing an Evidence Base. Edinburgh: Elsevier.

Yuen, J. C. (2005). Le regole terapeutiche: L’azione intrinseca dei punti in

Simongini, E. and Bultrini, L. (eds.) Le Lezioni di Jeffrey Yuen - Volume V.

Rome: AMSA.

ejom

e erapeutic Role of the Practitioner’s Heart in Classical Chinese Medicine and Modern Medical Science

Stéphane Espinosa