ELECTRIC VEHICLES MAGAZINE

ISSUE 35 | JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2018 | CHARGEDEVS.COM

2018 SMART

ELECTRIC DRIVE

p. 48

p. 32

IONIC MATERIALS

EMERGES AS A SOLID-

STATE BATTERY LEADER

p. 68

EVBOX COMPARES

US AND EUROPEAN

EVSE MARKETS

p. 64

HOW CHARGING

STATIONS EARN ENERGY

STAR CERTIFICATION

p. 28

TESLA’S MOTOR

CHIEF ON MODEL 3’S

PM MACHINE

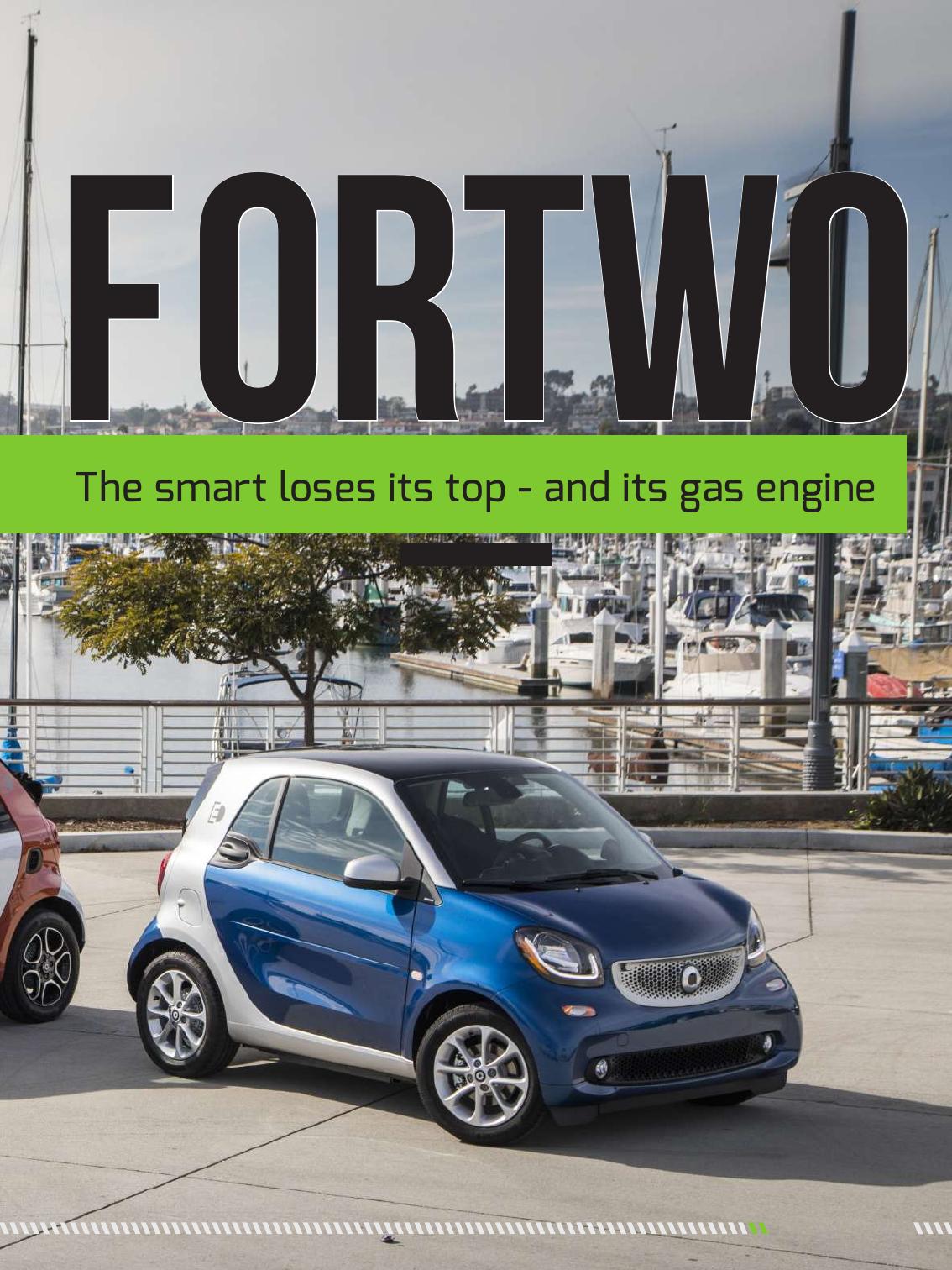

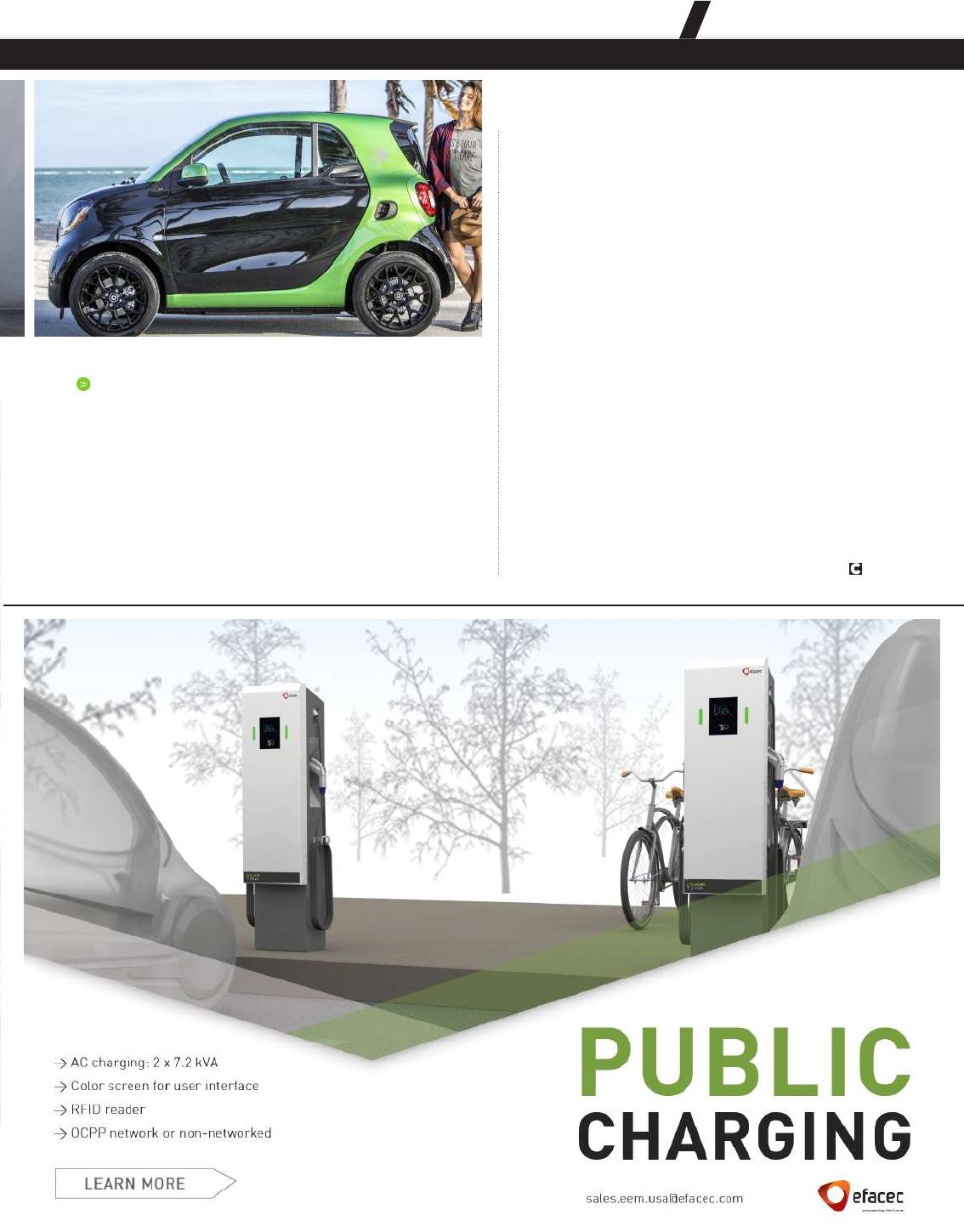

The smart loses its top - and its gas engine

FORTWO

Battery/EV Automated Test Equipment

chromausa.com | 949-600-6400 | sales@chromausa.com

© 2018 Chroma Systems Solutions, Inc. All rights reserved.

17040 Battery Test System

Next Generation Test for Battery and Battery Connected Devices

The 17040 is a highly ecient, precision battery test system. It’s regenerative, so power

consumption is greatly reduced. The energy discharged from testing is recycled back to the

grid reducing wasted energy and without generating harmonic pollution on other devices

– even in dynamic charge and discharge conditions. It’s also dual mode. Not only is the

17040 equipped with a Charge/Discharge mode but has a Battery Simulation mode to

verify if a connected device like a motor driver is functioning properly under varied

conditions. Software/hardware integration and customization capabilities include BMS,

data loggers, chambers, external signals, and HIL (Hardware in the Loop).

To nd out more about the 17040, Battery Pro Software, and other battery/EV test

solutions, visit chromausa.com.

Voltage Current Power

1000V 0~1500A 0~600kW

Conforms to International Standards

IEC, ISO, UL, and GB/T

High accuracy current/voltage measurement

±0.05%FS/±0.02%FS

New App Note Download:

Battery Electrical Tests

(Reference IEC61960)

60kW 300kW

Battery Pro Software

Waveform Current Test

Editor Shown

12

28

20

32

22 A closer look at energy

consumption in EVs

32 Ionic Materials

The Massachusetts-based company emerges as a leader in

solid-state batteries by focusing on polymer science

28 Model 3’s PM motor

Tesla’s top motor engineer talks about designing a

permanent magnet machine for Model 3

THE TECH

12 Aqueous anode enables super-fast charging

Predictingthepropertiesoflightweightcarbonbercomposites

14 DOE awards $2.25 million to develop lightweight vehicle materials

Toyota Tsusho to acquire 15% stake in Australian lithium mining company

15 BMW partners with Solid Power to develop solid-state batteries

16 Groupe PSA and Nidec form JV for automotive traction motors

17 New insight into lithium metal plating

18 Waterloo team develops low-cost approach to stabilize lithium metal anodes

Toyota and Panasonic explore joint prismatic battery development

19 SparkEVtelematicssolutionaimstoincreaseproductivityforEVeets

20 Recycling worn cathodes to make new batteries

Nexeon and partners win £7 million in funding to develop silicon anode tech

21 YASA secures £15 million growth funding, opens new Oxford production facility

current events

CONTENTS

Battery/EV Automated Test Equipment

chromausa.com | 949-600-6400 | sales@chromausa.com

© 2018 Chroma Systems Solutions, Inc. All rights reserved.

17040 Battery Test System

Next Generation Test for Battery and Battery Connected Devices

The 17040 is a highly ecient, precision battery test system. It’s regenerative, so power

consumption is greatly reduced. The energy discharged from testing is recycled back to the

grid reducing wasted energy and without generating harmonic pollution on other devices

– even in dynamic charge and discharge conditions. It’s also dual mode. Not only is the

17040 equipped with a Charge/Discharge mode but has a Battery Simulation mode to

verify if a connected device like a motor driver is functioning properly under varied

conditions. Software/hardware integration and customization capabilities include BMS,

data loggers, chambers, external signals, and HIL (Hardware in the Loop).

To nd out more about the 17040, Battery Pro Software, and other battery/EV test

solutions, visit chromausa.com.

Voltage Current Power

1000V 0~1500A 0~600kW

Conforms to International Standards

IEC, ISO, UL, and GB/T

High accuracy current/voltage measurement

±0.05%FS/±0.02%FS

New App Note Download:

Battery Electrical Tests

(Reference IEC61960)

60kW 300kW

Battery Pro Software

Waveform Current Test

Editor Shown

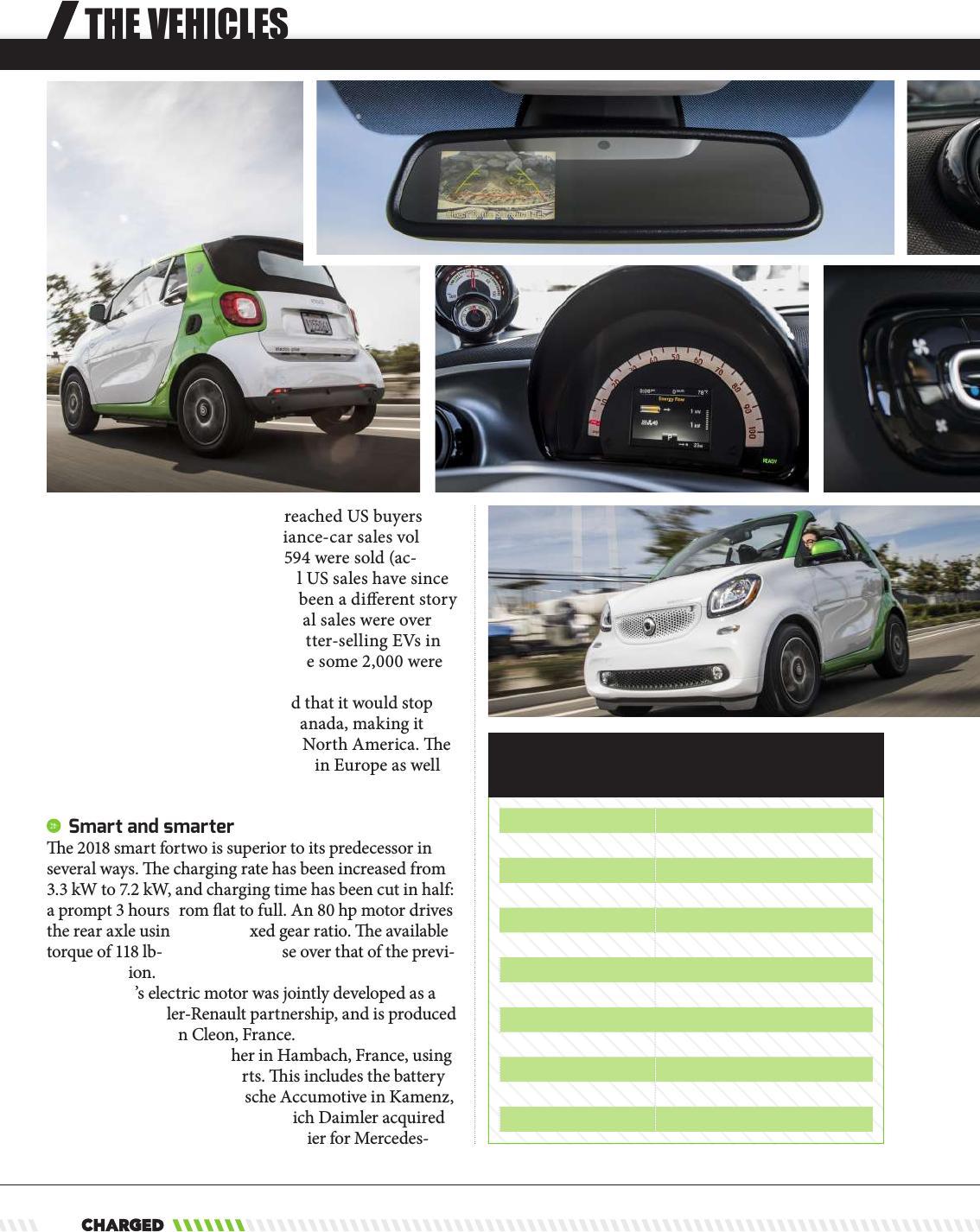

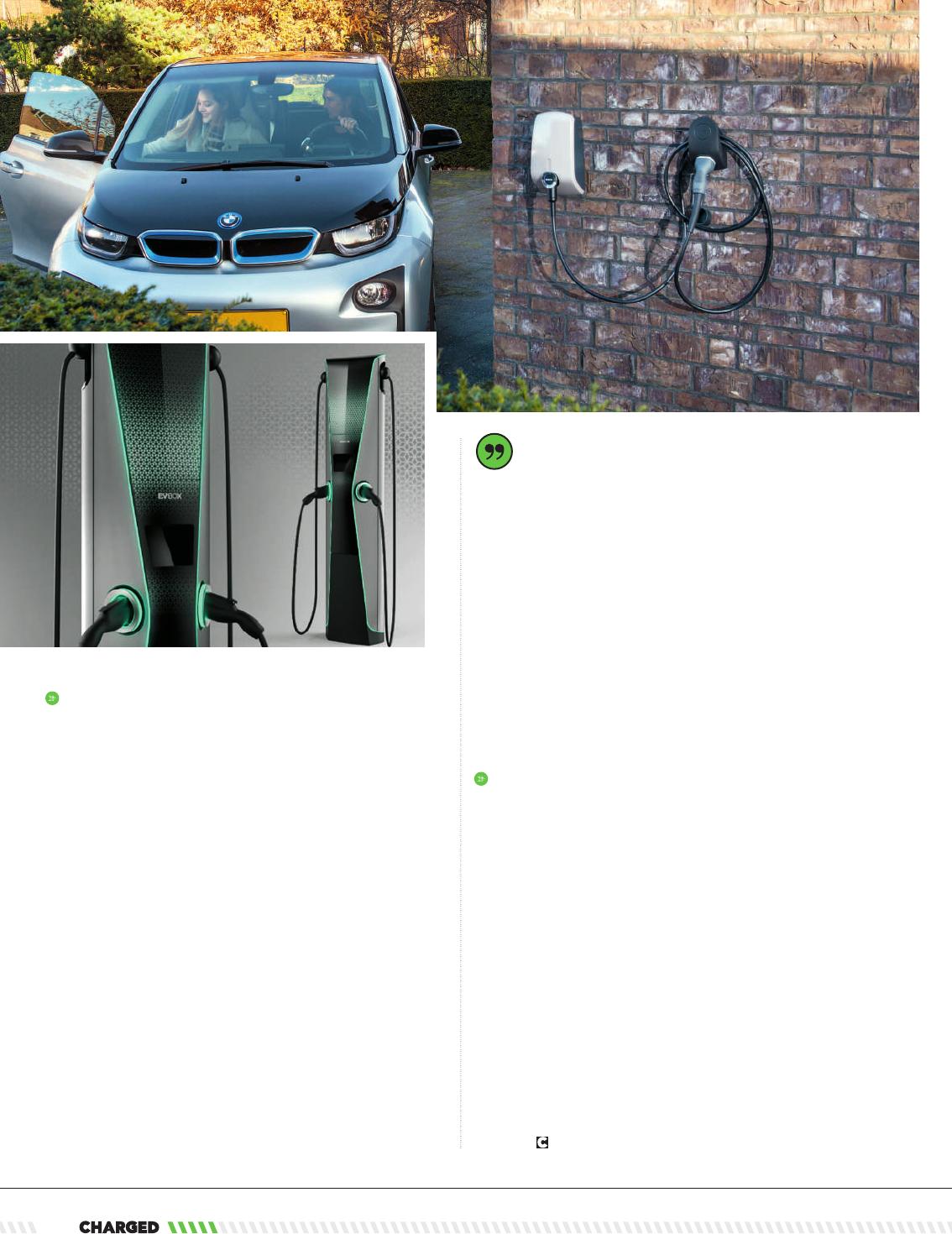

48 smart fortwo

The smart loses its top - and its gas engine

current events

THE VEHICLES

CONTENTS

38 2017 plug-in sales up 26%, Tesla and Chevy on top

40 All New Flyer facilities now capable of manufacturing electric buses

QuébecissuesnalregulationsforZEVmandate

42 Shenzhen goes fully electric with over 16,000 electric buses

Fuel cell truck maker Nikola gets investment from safety specialist WABCO

43 Electric container barges to sail from Europe this summer

44 Harley-Davidsonconrmsitwillbringelectricmotorcycletomarket

Los Angeles DOT orders 25 Proterra e-buses

45 Colorado releases new EV support plan to accelerate adoption

46 User survey shows buyers misunderstand the used EV market

Mercedes to build EVs in six plants on three continents

47 California Energy Commission awards $3 million to EV ride-sharing projects

46

44

48

42

82 Howsignicantare

so-called ICE bans?

IDENTIFICATION STATEMENT

CHARGED Electric Vehicles Magazine (ISSN: 24742341) January/February 2018, Issue #35 is published bi-monthly by Electric

Vehicles Magazine LLC, 2260 5th Ave S, STE 10, Saint Petersburg, FL 33712-1259. Periodicals Postage Paid at Saint Petersburg,

FL and additional mailing oces. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to CHARGED Electric Vehicles Magazine, Electric

Vehicles Magazine LLC at 2260 5th Ave S, STE 10, Saint Petersburg, FL 33712-1259.

—

So much more than hardware

Open, connected, reliable, and

experienced.

EV charging systems should never have a ‘set and forget’ approach to deployment.

Faster charging at higher powers demands greater technical competency and

plenty of real-world experience. With nearly a decade developing EV charging

solutions and several thousand DCFC stations installed around the world, we

understand the complexities of delivering more than power; but rather delivering an

optimal operator, site and driver experience. Our 24/7 service coverage, proven

hardware and intelligent connectivity make ABB the bankable choice for sustainable

mobility solutions. abb.com/evcharging

62

61

64

68

64 ENERGY STAR

HowEVchargingstationsearnENERGYSTARcertication

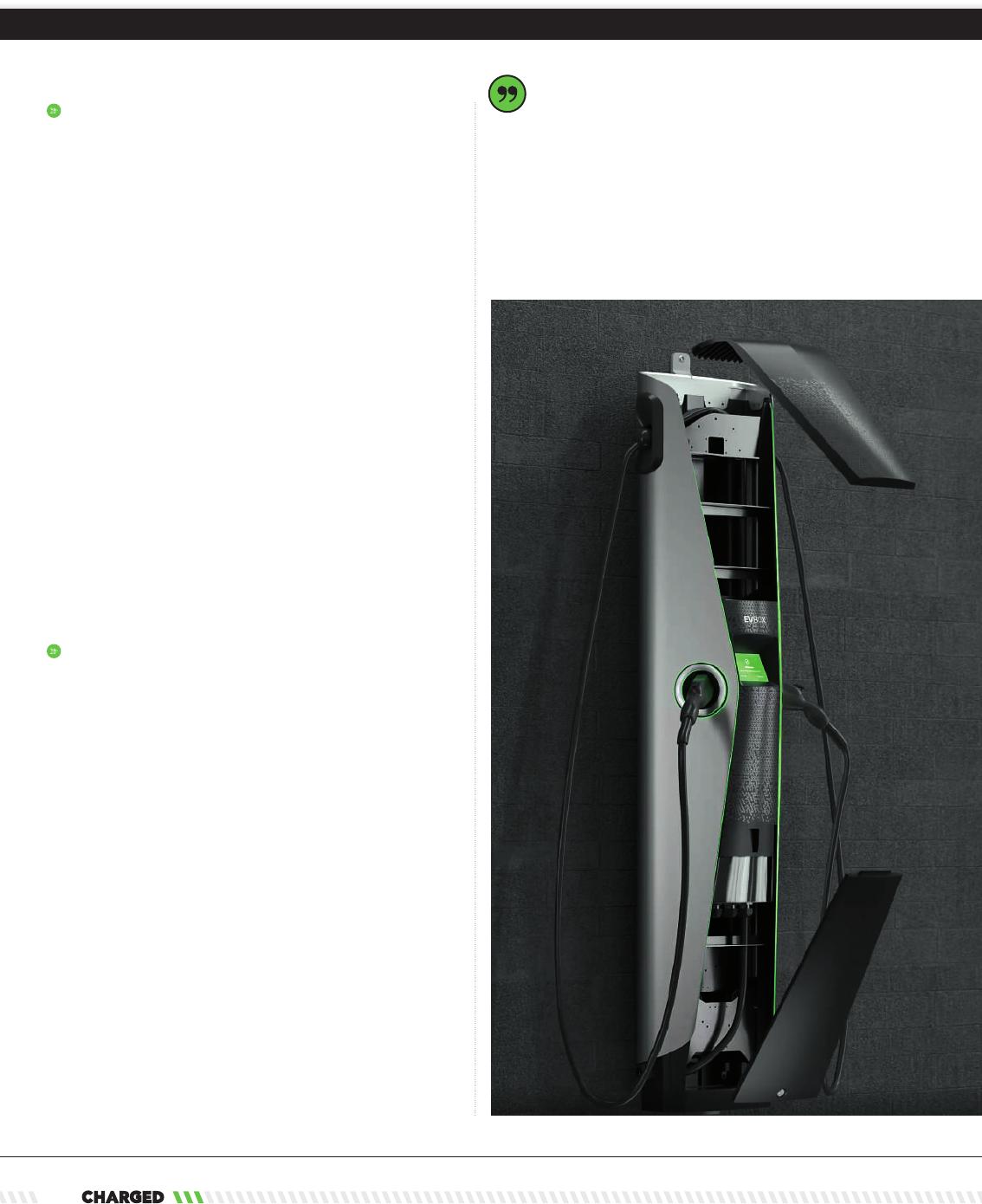

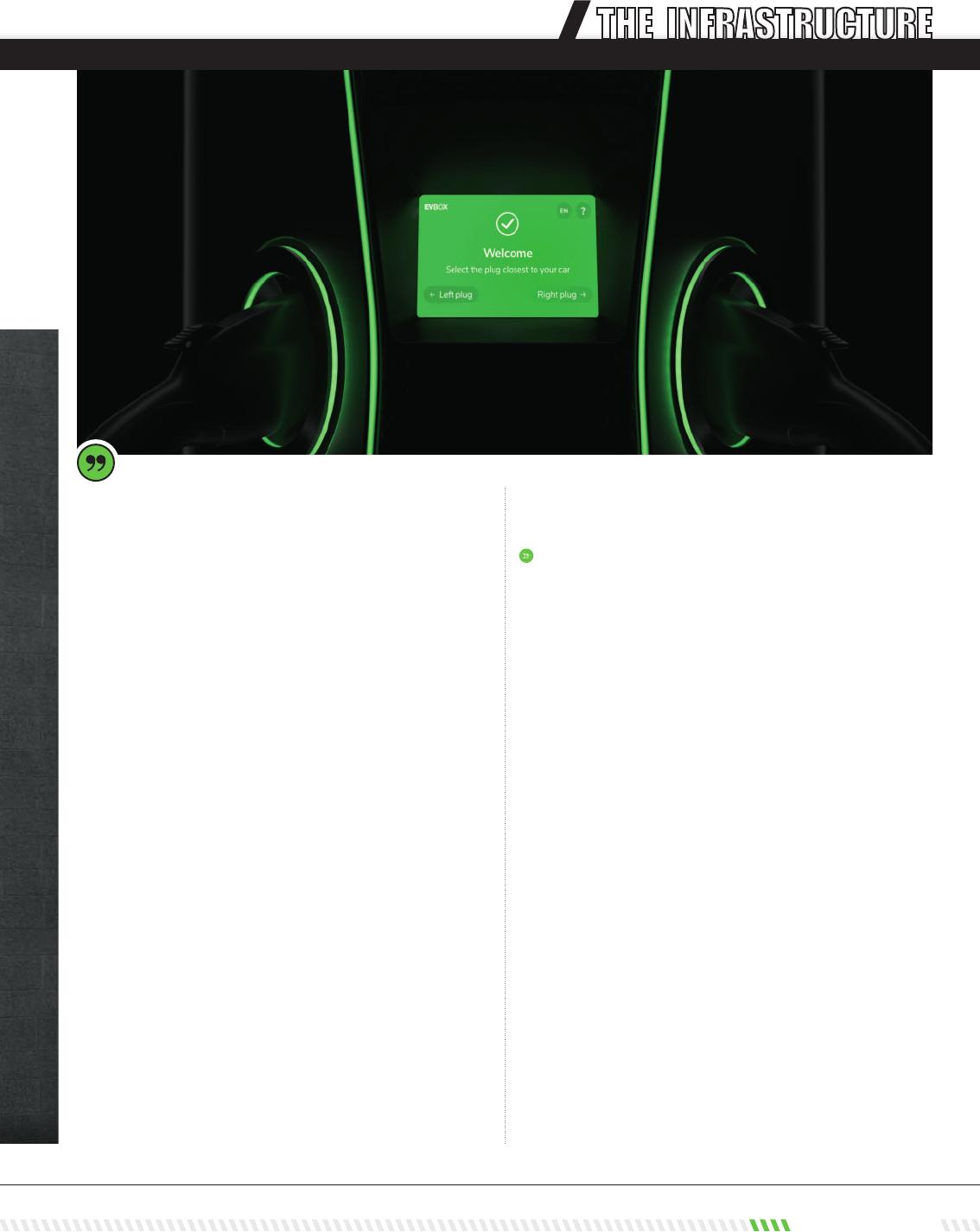

68 EVBox

The charging markets in Europe and the US: EVBox

explainsthedierence

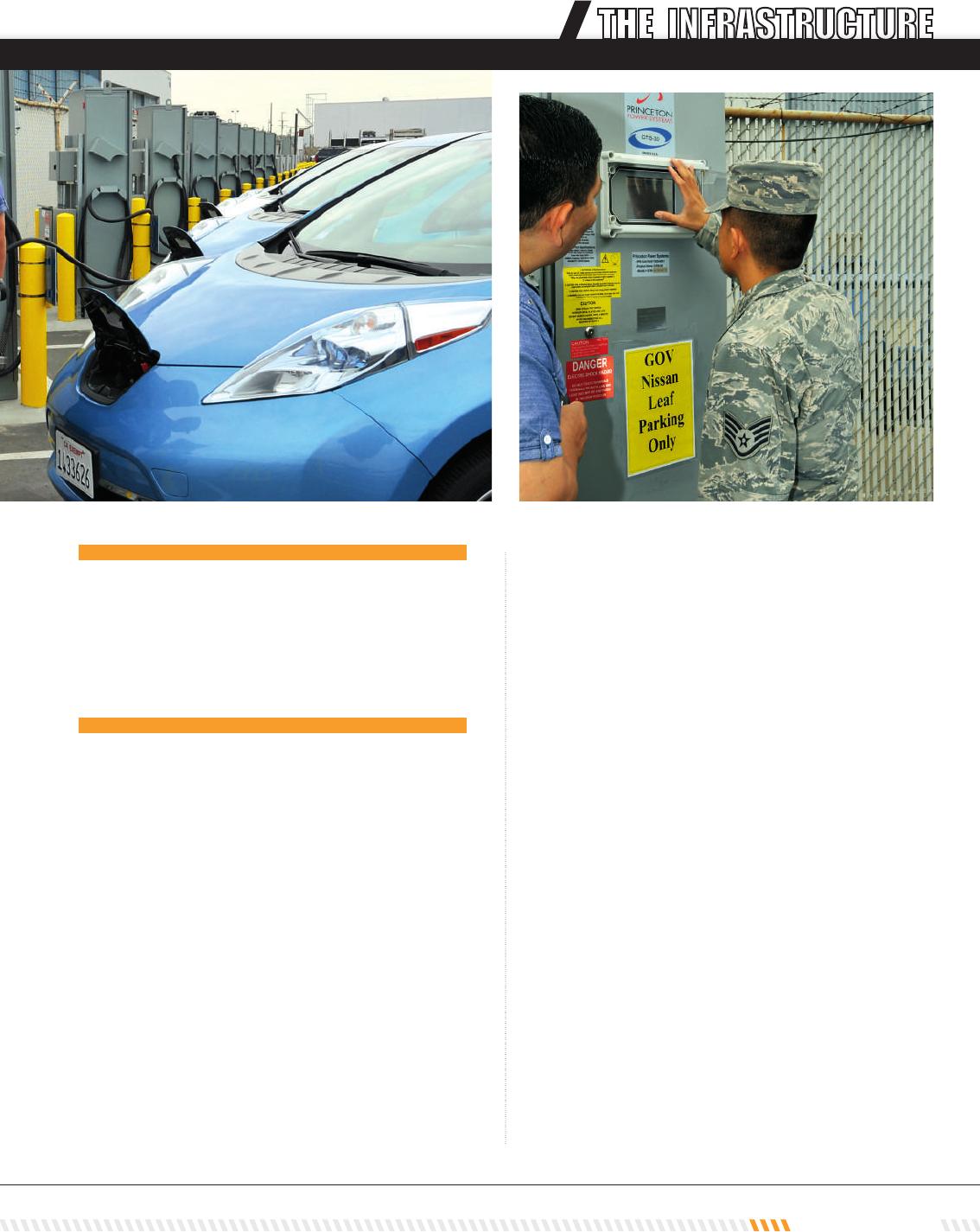

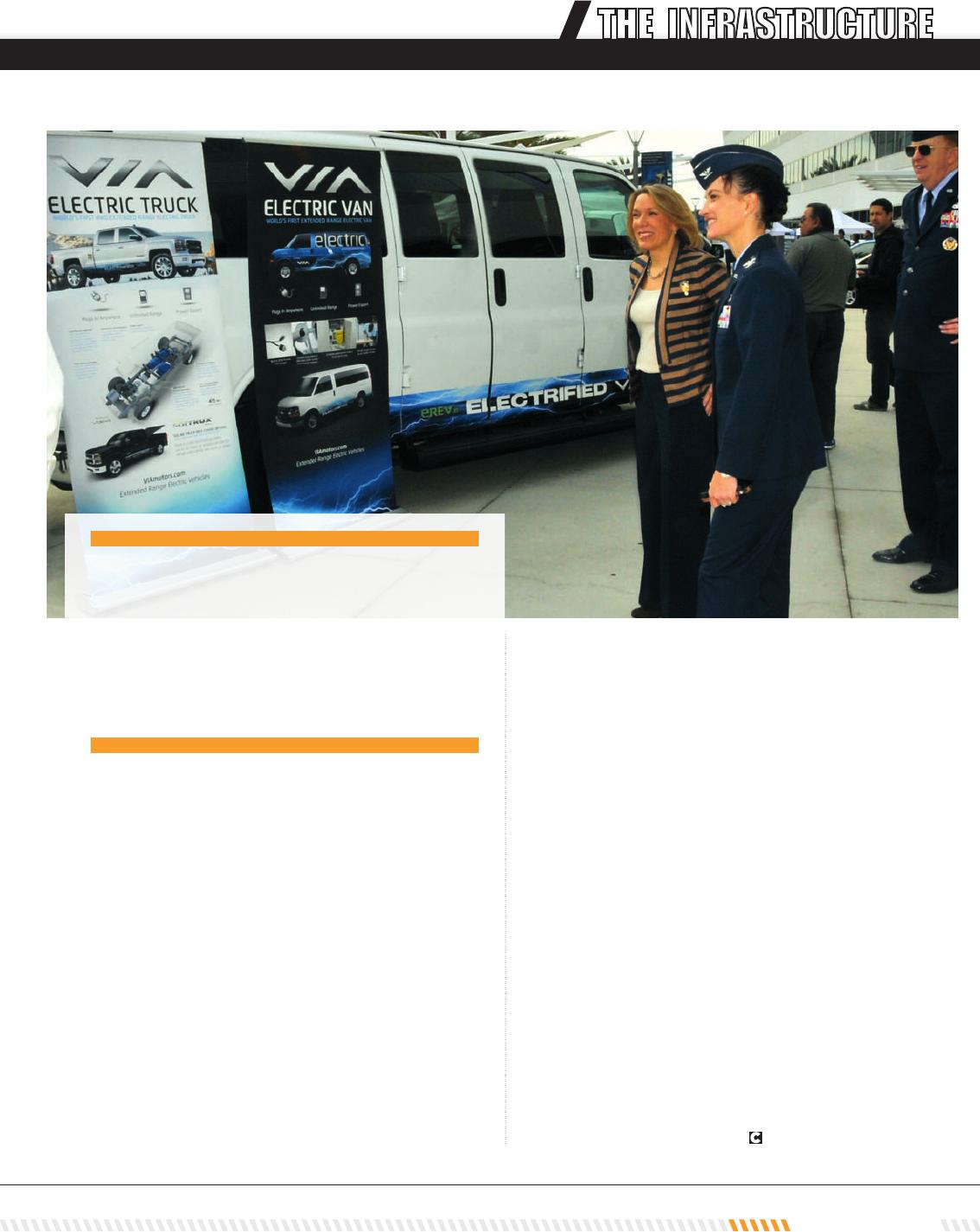

74 Vehicle-to-grid challenges

Air Force V2G project reveals challenges of the early days

58 GM wants Congress to fund EVSE, Toyota wants hydrogen fueling

Allego and Fortum collaborate on a European charging network

59 AeroVironment’s new TurboDX charging solution

60 SouthKoreatoociallyadoptCCSfastchargingstandard

Mack demonstrates catenary-powered PHEV at port of Los Angeles

61 New York announces $3.5 million in R&D funding for EV-grid integration

175 kW charging station opens in Germany, 350 kW coming soon

62 BP invests in mobile charging company FreeWire

VW subsidiary Electrify America to install 2,800 charging stations

63 PG&E’s EV Charge Network to install 7,500 new charging stations

GeniePoint Network rolls out fast chargers at UK petrol stations

REGISTER EARLY

MAXIMUM

SAVINGS

InternationalBatterySeminar.com

35th ANNUAL

ADVANCED BATTERY TECHNOLOGIES FOR CONSUMER, AUTOMOTIVE & MILITARY APPLICATIONS

BATTERY

EVENT

35th ANNUAL

LONGEST

RUNNING

March 26-29, 2018

Fort Lauderdale Convention Center | Fort Lauderdale, FL

FOR

How Does the Electrolyte Change during

the Lifetime of a Li-Ion Cell?

Jeff Dahn, PhD

NSERC/Tesla Canada, Dalhousie University

Uber Elevate - Powering an Electric UberAIR Future

Celina Mikolajczak

Uber

Addressing Key Battery Issues from a

Thermodynamics Perspective

Rachid Yazami, PhD

Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

Global Electrication and LG Chem

Denise Gray

LG Chem Power

PLENARY KEYNOTES

CHARGING

TOWARD

A GREENER

FUTURE

Providing expert guidance,

hardware, software, and

installation services for all

your EV charging needs

• COMMERCIAL

• RESIDENTIAL

• MULTI-UNIT

DWELLINGS

• MUNICIPALITIES

EV SAFE CHARGE

America’s premier

EV charging solutions

provider

CONTACT US TODAY

+1 844-EV-FOR-ME

evsafecharge.com

info@evsafecharge.com

EV Safe Charge named as one of

the TOP TEN STARTUPS by The Los Angeles

Auto Show and AutoMobility LA for 2017

“THE TOP 10 STARTUPS RACING

TO REMAKE THE AUTO INDUSTRY”

In September 2016, Tesla and SapceX CEO Elon Musk unveiled his ambi-

tious vision for colonizing Mars, which included building huge new rockets

and spacecra capable of holding 100 people at a time. During the presenta-

tion, Musk noted that moving a lot of humans to Mars is going to cost a lot

of money. He estimated that the cost of getting the interplanetary transport

system up and running would be around $10 billion total.

Musk also reiterated that his mission to get us to Mars is what motivates

most of his decisions. “I think as we show that this is possible, that this

dream is real, I think the support will snowball over time. e main reason

I’m personally accumulating assets is in order to fund this. I really don’t

have any other motivation except to be able to make the biggest contribu-

tion I can to making life multi-planetary.”

e man thinks very methodically, so it’s safe to assume his recent an-

nouncement to stay at the wheel of Tesla for another decade means that he’s

condent it’s the best bet to grow the fortune he wants to funnel into space

exploration. Previously, Musk had only publicly committed to staying on as

Tesla CEO until the Model 3 was successfully launched and on the road.

His compensation plan for the next decade is “perhaps the most radical

in corporate history,” as the New York Times put it. Musk will be paid only

if Tesla reaches a series of ambitious market value milestones - otherwise,

he will be paid nothing. Tesla has set a dozen market value targets, in

increments of $50 billion, starting at $100 billion, then $150 billion, and so

on up to a market cap of $650 billion. Also, the company has set a dozen

revenue and prot goals. Mr. Musk will receive 1.68 million shares, or about

1 percent of the company, only if he reaches both sets of milestones. Tesla’s

current market cap is about $59 billion.

Musk’s new compensation plan is similar to the previous one put in place

in 2012 (he reached all but one of those metrics), but now the numbers are

much larger. If he succeeds in increasing the value of Tesla to $650 billion - a

gure that would make Tesla one of the ve largest companies in the US -

his stock award could be worth as much as $55 billion.

e policy is about as shareholder-friendly as they come, in contrast to

those at many other corporations, which richly reward CEOs even when the

companies underperform. If the benchmarks are reached, the company’s

employees, including those who work on the factory oor, who get paid in

both cash and stock, could also become wealthy.

“If all that happens over the next 10 years is that Tesla’s value grows by 80

or 90 percent, then my amount of compensation would be zero,” Musk told

the NYT. “I actually see the potential for Tesla to become a trillion-dollar

company within a 10-year period.”

Coming from anyone else, that would seem like a totally crazy and un-

reachable milestone. It’s hard to imagine how Tesla could accomplish such

growth, but, at this point, it’s even harder to imagine betting against Musk.

Christian Ruoff | Publisher

EVs are here. Try to keep up.

Musk doubles down on Tesla to get us to Mars

170+ speakers including:

Discover the future of H/EV and

advanced baery technology at Europe’s

fastest-growing expert-led conference

15 – 17 May 2018 // Hannover, Germany

www.evtechexpo.eu

www.thebaeryshow.eu

Early-bird conference passes

available – book by Thursday 15

March 2018 to save up to €300

View

agenda and

pre-conference

workshops

online

Paul Freeland,

Principal Engineer,

Cosworth

Frank Bekemeier,

Chief Technology

Officer e-Mobility,

Volkswagen AG

Genis Turon, Senior

Engineer – Production

Engineering Advanced

Technology, Toyota

Marcus Hafkemeyer,

VP R&D Electric

Powertrain, BAIC

Dave Barnett,

Business

Development

Director, Wrightbus

Pascale Herman,

Valeo Thermal

Systems Marketing

Director, Valeo

Florian Joslowski,

Lead Engineer for

High-Voltage Systems,

Porsche Engineering

Services

Christophe Dos

Santos, Application

Engineer, LORD

Limhi Somerville,

Advanced Battery

Research, Jaguar

Land Rover

170+ speakers including:

Discover the future of H/EV and

advanced baery technology at Europe’s

fastest-growing expert-led conference

15 – 17 May 2018 // Hannover, Germany

www.evtechexpo.eu

www.thebaeryshow.eu

Early-bird conference passes

available – book by Thursday 15

March 2018 to save up to €300

View

agenda and

pre-conference

workshops

online

Paul Freeland,

Principal Engineer,

Cosworth

Frank Bekemeier,

Chief Technology

Officer e-Mobility,

Volkswagen AG

Genis Turon, Senior

Engineer – Production

Engineering Advanced

Technology, Toyota

Marcus Hafkemeyer,

VP R&D Electric

Powertrain, BAIC

Dave Barnett,

Business

Development

Director, Wrightbus

Pascale Herman,

Valeo Thermal

Systems Marketing

Director, Valeo

Florian Joslowski,

Lead Engineer for

High-Voltage Systems,

Porsche Engineering

Services

Christophe Dos

Santos, Application

Engineer, LORD

Limhi Somerville,

Advanced Battery

Research, Jaguar

Land Rover

Experience clarity like never before! Arbin’s new Laboratory Battery Test equipment allows

you to uncover battery trends that may be overlooked using traditional test equipment.

Industry leading measurement resolution, measurement precision, and timekeeping can

lead to new discoveries, and shorten the time required to bring new technology to

market. Innovative science demands the best instrumentation.

ETHICS STATEMENT AND COVERAGE POLICY

AS THE LEADING EV INDUSTRY PUBLICATION, CHARGED ELECTRIC VEHICLES MAGAZINE OFTEN COVERS, AND ACCEPTS CONTRIBUTIONS FROM, COMPANIES THAT ADVERTISE

IN OUR MEDIA PORTFOLIO. HOWEVER, THE CONTENT WE CHOOSE TO PUBLISH PASSES ONLY TWO TESTS: 1 TO THE BEST OF OUR KNOWLEDGE THE INFORMATION IS ACCU

RATE, AND 2 IT MEETS THE INTERESTS OF OUR READERSHIP. WE DO NOT ACCEPT PAYMENT FOR EDITORIAL CONTENT, AND THE OPINIONS EXPRESSED BY OUR EDITORS AND

WRITERS ARE IN NO WAY AFFECTED BY A COMPANY’S PAST, CURRENT, OR POTENTIAL ADVERTISEMENTS. FURTHERMORE, WE OFTEN ACCEPT ARTICLES AUTHORED BY “INDUS

TRY INSIDERS,” IN WHICH CASE THE AUTHOR’S CURRENT EMPLOYMENT, OR RELATIONSHIP TO THE EV INDUSTRY, IS CLEARLY CITED. IF YOU DISAGREE WITH ANY OPINION EX

PRESSED IN THE CHARGED MEDIA PORTFOLIO AND/OR WISH TO WRITE ABOUT YOUR PARTICULAR VIEW OF THE INDUSTRY, PLEASE CONTACT US AT CONTENTCHARGEDEVS.

COM. REPRINTING IN WHOLE OR PART IS FORBIDDEN EXPECT BY PERMISSION OF CHARGED ELECTRIC VEHICLES MAGAZINE.

Publisher

Associate Publisher

Senior Editor

Associate Editor

Account Executive

Technology Editor

Graphic Designers

Christian Ruoff

Laurel Zimmer

Charles Morris

Markkus Rovito

Jeremy Ewald

Jeffrey Jenkins

Mary Rose Robinson

Tome Vrdoljak

Andy Windy

For Letters to the Editor, Article

Submissions, & Advertising Inquiries

Contact: Info@ChargedEVs.com

Contributing Writers

Contributing Photographers

Cover Image Courtesy of

Special Thanks to

Peter Banwell

Paul Beck

Tom Ewing

Jeffrey Jenkins

Charles Morris

David Baillot

Sarah Corrice

Norsk Elbilforening

Vetatur Fumare

Jakob Härter

Nicolas Raymond

Mercedes-Benz USA

Kelly Ruoff

Sebastien Bourgeois

For more information on industry events visit ChargedEVs.com/Events

APEC 2018

March 4-8, 2018

San Antonio, TX

EV Tech Expo Europe

May 15-17, 2018

Hanover, Germany

2018

europe

15 – 17 May 2018 // Hanover, Germany

Europe’s largest trade fair for H/EV

and advanced baery technology

300+ exhibitors // 5,000+ aendees

Confirmed participation from:

“We are overwhelmed

with how many people are

here, very knowledgeable

people. It’s very different

to standard exhibitions.

All the engineers and

people from that

market are here.”

Max Göldi, LF Market Manager

Industry, HUBER+SUHNER

Co-located with

Register

online for

your free

trade fair

pass

www.evtechexpo.eu www.thebaeryshow.eu

info@evtechexpo.eu info@thebaeryshow.eu

Advanced

Automotive Battery

Conference

June 4 - 7, 2018

San Diego, CA

International Battery

Seminar

March 26-29, 2018

Fort Lauderdale, FL

REGISTER EARLY

MAXIMUM

SAVINGS

Internationa lBatterySeminar.com

35th ANNUAL

ADVANCED BATTERY TECHNOLOGIES FOR CONSUMER, AUTOMOTIVE & MILITARY APPLICATIONS

BATTERY

EVENT

35th ANNUAL

LONGEST

RUNNING

March 26-29, 2018

Fort Lauderdale Convention Center | Fort Lauderdale, FL

FOR

Sponsored Events

12

THE TECH

An international team of scientists, including research-

ers from the DOE’s Argonne National Laboratory, has

discovered an anode material that enables super-fast

charging and oers stable operation over many thou-

sands of cycles.

In a recent article in Nature Communications, Ar-

gonne Battery Scientist Jun Lu and colleagues describe a

water-bearing compound, lithium titanate hydrate, that

could replace the graphite anode commonly used in lith-

ium-ion batteries. Past research had identied lithium

titanate as a promising anode material, because of its

potential for fast charging and long cycle life, as well as

safer operation compared with graphite. In synthesizing

this material, researchers used a water-based process

that involved a nal step of heating the anode material to

above 500° C to drive out the water completely. is step

was needed because, during battery operation, the water

would react with the electrolyte and degrade perfor-

mance.

Argonne Distinguished Fellow Khalil Amine, a

co-author of the study, noted that heating to such a high

temperature caused unwanted coarsening and clumping

of the structure. e international team found that, by

heating the anode material to a much lower temperature

(less than 260° C), they could remove the water near the

surface, but retain the water in the bulk of the material

without the coarsening and clumping. When the scien-

tists tested the material in the laboratory, cycling stabil-

ity improved and capacity degraded only slightly over

10,000 cycles. e material also charged very quickly

- within less than two minutes. “Most of the time, water

is bad for non-aqueous lithium-ion batteries. But in this

case, it can be downright good,” said Jun Lu.

Looking to the future, Jun Lu observed that, because

water is everywhere in nature and common in chemi-

cal synthesis, the fabrication approach reported in this

research could open the door to discovery of other

high-performance electrode materials.

Aqueous anode enables

super-fast charging

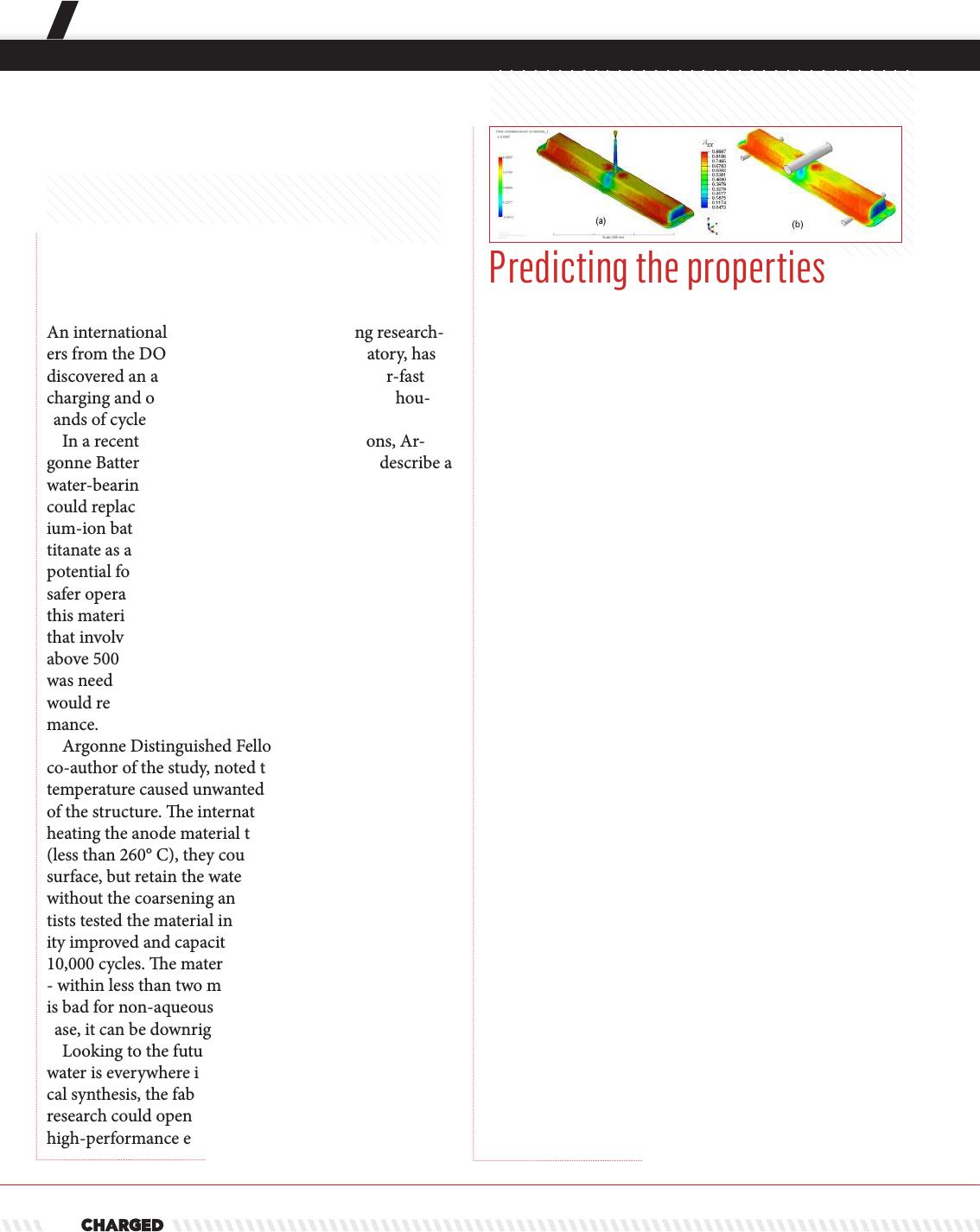

Carbon ber-reinforced plastics represent a promising

lightweight replacement for heavy steel. However, for

carbon ber to be widely adopted, new, more economical

composites need to be developed. Unfortunately, carbon

ber properties are dicult to model, as they depend on

complex features such as ber loading, length distribu-

tion and orientation.

Now researchers at the DOE’s Pacic Northwest Na-

tional Laboratory (PNNL), in partnership with Toyota,

Magna, carbon ber supplier PlastiComp, and soware

provider Autodesk, have developed a set of predictive

engineering tools that could speed the development.

Currently, in order to test new composite components,

carmakers must build molds, mold parts, and test them

- a long and costly process. Using the PNNL-led team’s

engineering soware, manufacturers will be able to

evaluate the structural characteristics of proposed new

carbon ber composites without building molds, allow-

ing designers to experiment much more quickly.

e team used Autodesk Moldow soware to predict

ber orientation and ber length distribution in molded

components. Using materials from PlastiComp, long

carbon ber components were molded and the bers

extracted for measurement. PNNL then compared the

predicted properties from the simulation soware to the

test results of the molded bers, and found that the so-

ware tool successfully predicted ber length distribution

in all cases and ber orientation in 88 percent of cases.

PNNL worked with Magna and Toyota to analyze the

performance gains and costs of long carbon ber com-

ponents versus standard steel and berglass composites.

PNNL found the polymer composite studied could re-

duce the weight of auto components by over 20 percent.

However, production costs can be 10 times higher than

those of steel.

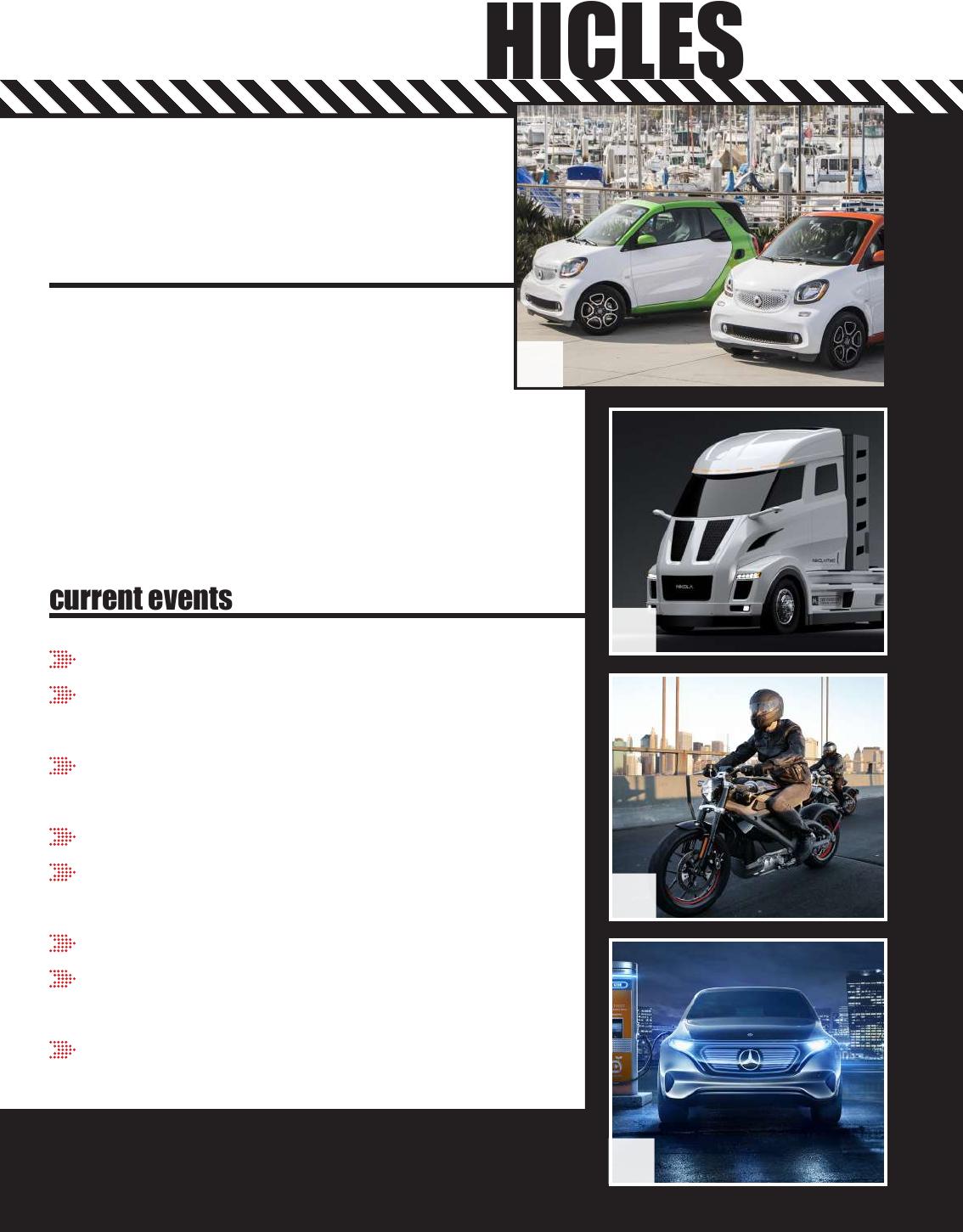

Predicting the properties

of lightweight carbon fiber

composites

Image courtesy of PNNL

Leading the Industry in Motor Production Methods for The New Millennium.

•Hairpin / Solid

Conductor Winding

•Precision Winding & Insertion

•Segment Winding

www.odawara.com

www.odawara-eng.co.jp

New Year with

Leader in EV & Hybrid

Stator Winding

Looking to The

You in Mind.

Run

Module and pack level testing

CAN, I2C SMBus capable

Drive cycle simulation

Import drive cycle from table of values

Battery power is recycled to AC grid in discharge

Utilizes Maccor’s standard battery test software suite

No system power limit, up to 900KW

14

THE TECH

Toyota Tsusho, a member

of the Toyota Group, has

signed a share subscription

agreement with Orocobre

to become a 15% share-

holder. e total investment

amount will be about $292

million Australian.

e company expects

lithium demand to contin-

ue growing with the shi

to EVs, in addition to the

steady growth of battery-powered consumer electronics.

Demand growth to date has seen the price of lithium

more than double over the past few years.

Toyota Tsusho and Orocobre have been long-term

partners in the development of the Olaroz Lithium

Facility in Argentina, a lithium brine project, which was

brought into successful production in 2014, and Toyota

Tsusho has established a worldwide sales network for

lithium from Olaroz since the rst production.

e capital from Toyota Tsusho’s strategic investment

will be used primarily for the expansion of the Olaroz

Project (Phase 2), which aims to increase capacity by

25,000 tons per year (lithium carbonate equivalent)

bringing the total capacity of the Olaroz Project to

42,500 tons per year.

e Phase 2 expansion plan is expected to be com-

missioned in the second half of 2019. Toyota Tsusho

will be appointed as the exclusive sales agent for Phase

2 production and will to respond to the growing market

demand.

Toyota Tsusho to acquire

15% stake in Australian

lithium mining company

Orocobre

Five American-based organizations are receiving $2.25

million in technical assistance from Department of En-

ergy national laboratories to further develop lightweight

materials technologies and more ecient vehicles. e

awards are part of the DOE’s LightMAT - the Light-

weight Materials Consortium.

• Sandia National Laboratories, Oak Ridge National

Laboratory, and Pacic Northwest National Laboratory

will partner with Mallinda LLC to characterize micro-

scopic structural defects and evaluate the high-speed

impact on the company’s malleable thermoset carbon

ber-reinforced plastic technology.

• Magna Services of America will team up with PNNL

to fabricate a non-rare earth magnesium bumper beam

using PNNL’s ShAPE technology. ShAPE, or Shear As-

sisted Processing and Extrusion, is a new technology

that fabricates bumper beams with sucient strength,

ductility, and energy absorption properties without

the need for costly rare earth additives and elevated

temperature processing.

• GM will partner with PNNL to develop a predictive

performance model of dissimilar metallic spot-welds

for joining aluminum to steel. Currently, automotive

researchers are unclear about the factors that are most

critical for predicting joint failures when welding alu-

minum and steel together.

• Eck Industries will work with PNNL to lower costs

and address mechanical property issues in aluminum

castings. e additional iron content found in recycled

aluminum limits usability in performance applications

because of reduced overall strength and durability.

• e computational capabilities at Los Alamos National

Laboratory will be used to help the Edison Welding

Institute improve the robustness of a manufacturing

method called magnetic pulse welding which can

eectively join dierent metals together.

DOE awards $2.25 million to

develop lightweight vehicle

materials

Solid Power has grown rapidly since it was established in

2012 as a spin-out company from the University of Col-

orado. e battery developer recently moved into a new

facility in Louisville, Colorado

that will triple its footprint.

Now the company has an-

nounced a partnership with the

BMW Group to develop its sol-

id-state batteries for EV applica-

tions. e new facility will enable

Solid Power to deliver commer-

cial-quality battery prototypes.

The Power in Electrical Safety

©

www.bender.org

Bender’s ground fault detector, the ISOMETER® IR155-3204 and

iso165C, provide safety in hybrid and electric vehicles as well as

in Formula 1.

The IR155-3204 and iso165C monitor the

complete vehicle electrical drive system and

provide effective protection against electric

shocks and fire hazards.

Safety for vehicles

We support

the Formula

Hybrid Teams

The Power in Electrical Safety

©

www.bender.org

Bender’s ground fault detector, the ISOMETER® IR155-3204 and

iso165C, provide safety in hybrid and electric vehicles as well as

in Formula 1.

The IR155-3204 and iso165C monitor the

complete vehicle electrical drive system and

provide effective protection against electric

shocks and fire hazards.

Safety for vehicles

We support

the Formula

Hybrid Teams

The Power in Electrical Safety

©

www.bender.org

Bender’s ground fault detector, the ISOMETER® IR155-3204 and

iso165C, provide safety in hybrid and electric vehicles as well as

in Formula 1.

The IR155-3204 and iso165C monitor the

complete vehicle electrical drive system and

provide effective protection against electric

shocks and fire hazards.

Safety for vehicles

We support

the Formula

Hybrid Teams

ther validation that solid-state battery innovations will

continue to improve electric vehicles.”

BMW partners with Solid Power to develop solid-state batteries

Solid Power’s solid-state batter-

ies are comprised of proprietary

inorganic materials, and contain

no volatile or ammable compo-

nents. According to the company,

the technology has great poten-

tial to provide BMW’s EVs with

increased driving range and a

battery with a longer shelf life that

can withstand high temperatures.

“Since the company’s inception,

the Solid Power team has worked

to develop and scale a competitive

solid-state battery, paying special

attention to safety, performance,

and cost,” said Doug Campbell,

founder and CEO of Solid Power.

“Collaborating with BMW is fur-

????

Photo courtesy of BMW

THE TECH

OpenECU EV / HEV Supervisory Control

The OpenECU M560

• Designed for complex hybrid and EV applications

• Meets ISO26262 ASIL D functional

safety requirements

• 112 pins of exible I/O

including 4 CAN buses

• Comprehensive fault diagnosis

supporting functional safety as

well as OBD requirements

Contact Pi Innovo today and see how the

M560 can support your Hybrid/EV program.

????

Groupe PSA, owner of the Peugeot, Citroën, DS, Opel

and Vauxhall brands, and Nidec Leroy-Somer, a French

manufacturer of small precision motors, plan to form a

joint venture to develop a range of traction motors for

electried vehicles. e 50/50 JV will receive an initial

investment of €220 million ($262 million).

e main components of the electric powertrain will

be designed and produced in France. e JV will supply

traction motors to Groupe PSA’s vehicles, and possibly to

other OEMs as well.

Groupe PSA expects the market for automotive elec-

tric motors to double to $53.5 billion by 2030.

Groupe PSA and Nidec form JV for automotive traction motors

Run

Reducing charging time by increasing charging current

can have a negative eect on battery lifetime and safe-

ty. One reason for this is a phenomenon called lithium

plating.

“e rate at which lithium ions can be reversibly

intercalated into the graphite anode, just before lithium

plating sets in, limits the charging current,” explains

Johannes Wandt of Munich Technical University.

Wandt is one of a team of researchers at Munich and

two other German universities who have developed an

analytical technique that provides new insights into lithi-

um plating and how it aects charging rates.

In a paper published in Elsevier’s Materials Today, the

researchers explain that if the charging rate is too high,

lithium ions deposit as a metallic layer on the surface

of the anode rather than inserting themselves into the

graphite. “is undesired lithium plating side reaction

causes rapid cell degradation and poses a safety hazard,”

Dr. Wandt said.

New insight into lithium metal plating

Dr. Wandt and his colleagues set out to develop a new

tool to detect the actual amount of lithium plating on a

graphite anode in real time. e result is a technique the

researchers call operando electron paramagnetic reso-

nance (EPR).

EPR detects the magnetic moment associated with

unpaired conduction electrons in metallic lithium with

very high sensitivity and time resolution.

“In its present form, this technique is mainly limited to

laboratory-scale cells, but there are a number of possible

applications,” explains researcher Dr. Josef Granwehr.

“So far, the development of advanced fast charging

procedures has been based mainly on simulations, but

an analytical technique to experimentally validate these

results has been missing. e technique will also be very

interesting for testing battery materials and their inu-

ence on lithium metal plating - in particular, electrolyte

additives that could suppress or reduce lithium metal

plating.”

18

THE TECH

Researchers at the University of Waterloo in Canada

have developed a way to stabilize lithium metal elec-

trodes by forming a single-ion-conducting and stable

protective surface layer in vivo.

In “An In Vivo Formed Solid Electrolyte Surface Layer

Enables Stable Plating of Li Metal,” published in the

journal Joule, Quan Pang, Xiao Liang and colleagues

explain how they used an electrolyte additive complex

that reacts with the lithium surface to form a membrane.

e team demonstrated stable lithium plating/stripping

for 2,500 hours at 1 mA cm-2 in symmetric cells, and

ecient lithium cycling at high current densities up to 8

mA cm-2. More than 400 cycles were achieved at a 5-C

rate in cells with a Li

4

Ti

5

O

12

counter electrode at close to

100% coulombic eciency.

“Herein, we demonstrate a facile and scalable approach

to build a single-ion-conducting SEI layer with con-

trolled compositions in vivo (i.e., inside the assembled

cell) that maintains complete and intimate contact with

the locally uneven lithium metal surface,” write Pang

and colleagues. “is comprises a thin amorphous Li

3

PS

4

layer formed by using a low-concentration electrolyte

additive. It reduces the reactions with the electrolyte and

eliminates the heterogeneity of the SEI, thus allowing a

non-impeding and uniform Li+ ux.”

“e nature of in vivo formation distinguishes it from

ex situ deposition of solid electrolytes (SE), such as

atomic layer deposition. More importantly, the Li

3

PS

4

layer is a Li+ single-ion conductor with a theoretical

Li+ transference number of unity, which ideally elimi-

nates the ion depletion and strong electric eld buildup

at the Li surface that inspire dendrite growth. is also

contrasts with other types of articial or additive-driven

ion-passivating SEIs. We show experimental evidence of

these two important aspects and demonstrate that their

interplay allows long-life dendrite-free lithium plating.”

Waterloo team develops a

low-cost way to stabilize

lithium metal anodes

Toyota and Panasonic have

agreed to begin studying the

feasibility of a joint auto-

motive prismatic battery

business.

Panasonic has positioned

lithium-ion batteries as one

of its key businesses, and its automotive batteries are

used by many automakers worldwide. Toyota, maker of

the Prius hybrid and the Mirai fuel cell vehicle, has been

a holdout when it comes to developing pure EVs, but

there are signs that this policy is changing. Now the two

companies say they aim to develop the best automotive

prismatic battery in the industry.

“To solve issues currently confronting us worldwide,

such as global warming, air pollution, the depletion of

natural resources and energy security, it will be necessary

to further the popularization of electried vehicles,” said

Toyota President Akio Toyoda. “e automotive indus-

try is now facing an era of profound transformation, the

likes of which come only once every 100 years. No longer

can we expect a future by adhering to our current path.

Panasonic has accumulated its industry-leading capabil-

ity to develop automotive batteries over many years, and

Toyota has accumulated vehicle electrication technolo-

gies through the development of hybrid vehicles. Toyota

also loves cars and is determined to never let them

become commodities.”

“Today, the surging demand for electried vehicles is

changing the landscape of the automobile industry and,

moreover, drastically transforming its entire structure,”

said Panasonic President Kazuhiro Tsuga. “e battery is

a key device in promoting the widespread use of elec-

tried vehicles, and thus toward achieving a sustainable

society. Panasonic can never survive if we simply cling to

our current business models. erefore, always hav-

ing the mindset of a challenger, we will strive to create

contributions toward the widespread use of electried

vehicles, fully utilizing our assets and strengths nurtured

over the past 100 years.”

Toyota and Panasonic explore

joint prismatic battery

development

Photo courtesy of Toyota

Advanced energy solutions

to meet your growing needs

for testing, conditioning,

simulation and lifecycling.

Expanding the FTF-HP

power

to

you!

MEGA

Expanding the FTF-HP

4MW

· EV / HEV/ PHEV Pack Testing

· Inverter, UPS, Generator and

Flywheel Testing

· Microgrid Battery Conditioning

· Drive Cycle Simulation

· Bidirectional DC Power Supply

· Super and Ultra-Capacitor Testing

Advanced Energy

Technology Applications

2017 Bitrode Corporation ™

info@bitrode.com www.bitrode.com

1 MW

is an operating unit of

•Single or dual circuit models

available

• Over-current, under-

current, over voltage and

under-voltage protection

standard on all models

• Innite number of

program steps when used in

conjunction with VisuaLCN

software

• Remote Binary Protocol

available for control via 3rd

party software

• Battery simulator option

• Discharge power recycled to

AC line for cooler, more energy

ecient operation

• Current Rise Time (10-90%)

less than 4ms with zero

overshoot

• Optional Zero Volt testing

capability

• Other FTF options and custom

hardware/software capabilities

available.

Contact Bitrode to discuss your

requirements.

• Up to 1MW with available option for parallel

testing up to 2MW

www.sovemagroup.com

Spark EV is a new AI-based journey prediction telemat-

ics solution designed to help eet EVs complete more

journeys between charges, enabling greater eet utiliza-

tion.

A combination of sensor technology, cloud-based

analysis soware and a smartphone app, Spark EV ana-

lyzes live driver, vehicle and other data sources, such as

weather and congestion, then uses soware algorithms to

increase the accuracy of journey predictions. Using ma-

chine learning, the system automatically updates predic-

tions aer each journey, continually improving eciency.

Drivers and eet managers enter their journey through

the app, Spark EV’s web interface, or their existing eet

management soware, and the system advises whether

they will be able to complete it, based on live data, previ-

ous trips and charging locations.

Spark EV telematics solution aims to increase productivity for

EV fleets

Sold as a monthly subscription, Spark EV is designed

to easily integrate with existing eet management/sched-

uling systems through its open API, and can also be

used as a standalone solution for smaller eets. It can be

installed with all current EVs.

“Fleet managers understand that the future increas-

ingly revolves around electric vehicles,” said Spark EV

Technology CEO Justin Ott. “However, existing methods

of predicting range between charges are not accurate

enough for eet use, leading to range anxiety and a

consequent drop in productivity as managers cut back

the number of journeys to avoid potentially running out

of power. Spark EV increases productivity through more

accurate predictions that enable 20% more journeys

between charges.”

20

THE TECH

As lithium-ion batteries proliferate, the question of what

to do with them when they wear out is becoming a major

environmental concern. Less than ve percent of used

batteries are recycled today.

Nanoengineers at the University of California San

Diego have developed an energy-ecient recycling pro-

cess that restores used cathodes from spent batteries and

makes them work just as good as new.

As the researchers explain in a paper published in

Green Chemistry, the new method can be used to

recover lithium cobalt oxide, which is widely used in

consumer electronics. e method also works on nickel

manganese cobalt (NMC), a cathode material which is

used in many EVs.

Researchers pressurized recovered cathode particles in

a hot alkaline solution containing lithium salt, then put

them through an annealing process in which they were

heated to 800° C and then cooled very slowly. ey made

new cathodes from the regenerated particles and found

them to have the same energy storage capacity, charging

time and lifetime as the originals.

“ink about the millions of tons of lithium-ion

battery waste in the future, especially with the rise of

electric vehicles, and the depletion of precious resourc-

es like lithium and cobalt,” said Professor Zheng Chen.

“Mining more of these resources will contaminate our

water and soil. If we can sustainably harvest and reuse

materials from old batteries, we can potentially prevent

such signicant environmental damage and waste.”

Recycling cathodes would also save money. “e price

of lithium, cobalt and nickel has increased signicantly,”

said Chen. “Recovering these expensive materials could

lower battery costs.”

Chen’s team is rening the process so that it can be

used to recycle any type of cathode material, and is also

working on a process to recycle used anodes.

Recycling worn cathodes to

make new batteries

Silicon anode specialist Nexeon, along with a couple of

partners, has been awarded £7 million in Innovate UK

funding for the SUNRISE project, which will develop

battery materials based on silicon as a replacement for

carbon in the cell anode.

Nexeon will lead the silicon material development and

scale-up stages of the project, while polymer provider

Synthomer will lead the development of a next-gener-

ation polymer binder optimized to work with silicon,

and ensure anode/binder cohesion during a lifetime of

charges.

Nexeon and partners win

£7 million in funding to

develop silicon anode tech

Photos courtesy of Nexeon

Silicon is currently being adopted as a partial re-

placement for carbon - typically up to 10% - in battery

anodes, but problems caused by expansion when the

cells are charged and discharged remain a hurdle. Project

SUNRISE addresses the silicon expansion and binder

system issues, and allows more silicon to be used, further

increasing energy density.

“e biggest problems facing EVs - range anxiety, cost,

charge time or charging station availability - are almost

all related to limitations of the batteries,” says Nexeon

CEO Dr. Scott Brown. “Silicon anodes are now well

established on the technology road maps of major auto-

motive OEMs and cell makers, and Nexeon has received

support from UK and global OEMs, several of whom

will be involved in this project as it develops.”

Photo courtesy of David Baillot/UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering

YASA, a manufacturer of axial-ux electric motors and

controllers, has raised £15 million in growth funding,

bringing the total raised by the company to £35 million.

e new investment follows YASA’s signing of long-

term development and supply agreements with custom-

ers in the automotive sector. e company has recently

opened a new 100,000-unit capacity production facility

in Oxford, UK to meet the growing demand for its

products. YASA says that 80% of production is destined

for export to automotive manufacturers across the world,

including China.

In addition to automotive, YASA motors are used in

marine applications and in aerospace, elds in which

high power density and torque density are critical.

YASA secures £15m growth

funding, opens new Oxford

production facility

Dr. Chris Harris, YASA’s CEO, said, “Our customers

are looking to adopt innovative new technologies such as

YASA’s axial-ux electric motors and controllers in order

to meet the needs of the rapidly expanding hybrid and

pure electric automotive market. is additional £15 mil-

lion in growth funding will enable YASA to further in-

vest in the volume production capacity necessary to meet

our customers’ requirements, and to address markets

beyond automotive including aerospace and marine.”

Photo courtesy of YASA

Sales, Service, & Logistics

provided by Local Hongfa America Team

(714) 669-2888 | sales@hongfaamerica.com

www.hongfa.com

Charging Station

22

Photo courtesy of Norsk Elbilforening - CC BY 2.0

There are five primary factors

that go into determining how

much power is required to propel

a vehicle: velocity, mass, rolling

resistance, wind resistance and

the gradient of the road.

Photo courtesy of Vetatur Fumare - CC BY-SA 2.0

JAN/FEB 2018 23

THE TECH

LOOK

By Jeffrey Jenkins

hen it comes to factors that aect energy con-

sumption in EVs, the big kahunas are weight and

wind resistance (aka CdA), but there are other

factors that can have a surprisingly outsized

eect and that tend to be overlooked, such as the use of cli-

mate control (AC, of course, but especially heat). Conversely,

one factor which does not seem to aect energy consump-

tion all that much is the use of regenerative braking.

First, though, two terms that are confused or even used

interchangeably way too oen are power and energy. Power is

W

AT ENERGY

CONSUMPTION

IN EVS

A CLOSER

24

the reduced tire life and increased risk of a blowout.

Next is the contribution from wind resistance, which is

proportional to the square of speed, v (in m/s), air density,

ρ (1.2 kg/m³ for air at 20° C at sea level), drag coecient,

Cd (typically in the range of 0.3 to 0.4), and the frontal

area of the vehicle, A (in m²). e relevant equation to

nd the drag force from wind resistance is:

Fw = 0.5 * v² * ρ * Cd * A

For example, a vehicle traveling at 90 kph (25 m/s)

with a Cd of 0.35 and a frontal area of 2.2 m² requires

a force of 288.75 N to overcome wind resistance; at 120

kph that force increases to 513.33 N, or nearly double!

e last drag force is from a change in elevation, which

is the only one which can actually assist the vehicle (aside

from the unlikely scenario in which a tailwind is strong

enough to propel the vehicle all on its own). is equation

is a little less straightforward and requires some trigo-

nometry. If the incline of the road is not given in degrees,

then converting to such is the rst step. In the US, grade

is given as a percentage rise vs. a horizontal run, and

these gures correspond to the opposite and adjacent

sides of a right triangle (the vehicle itself drives along the

hypotenuse) so to convert percentage grade into degrees

a measure of the rate at which work can be done while en-

ergy is a measure of the amount of work done. Ignoring the

eect of wind resistance (which would otherwise disprove

what comes next), it will take the same amount of energy

to drive a 2,000 kg vehicle a distance of 1 km whether it is

going 1 kph or 2 kph or even 10 kph. Yes, the higher speed

requires more power, but it is applied for an inversely lower

amount of time, and energy is power * time.

Power

ere are ve primary factors that go into determining

how much power is required to propel a vehicle: veloc-

ity (aka speed), mass (aka weight, at least as long as the

vehicle remains on planet Earth), rolling resistance,

wind resistance and the gradient of the road. e latter

four components are used to determine the total drag

force opposing the vehicle’s motion, and speed should

be self-explanatory. e relevant physics equation that

combines all these factors together is deceptively simple:

P = F * v

Where P is power (in watts, W), F is the total drag

force acting on the vehicle (in Newtons, N), and v is the

velocity (in meters per second, m/s). e components that

make up the total drag force need to be evaluated for the

above equation to be useful, however. Also note that the

power required actually increases with the cube of the

speed of the vehicle, because speed is present in the power

equation above as well as speed squared in the equation

for wind resistance. Speed really does kill…eciency,

anyway.

Drag forces

e easiest drag force to evaluate is rolling resistance, Fr,

which is simply vehicle mass (in kilograms, kg) * gravita-

tional acceleration of your particular planet (9.81 m/s² for

Earth) * coecient of friction, Cf (a dimensionless number,

usually between 0.01 and 0.02 for most tires and roads):

Fr = m * 9.81 m/s² * Cf

For example, a 2,000 kg vehicle and a coecient of

friction between tires and road of 0.015 results in a drag

force from rolling resistance of 294 N, or a mere 30 kg of

force (1 N = 0.102 kg-f). is isn’t much force to over-

come, though rolling resistance does increase dramati-

cally if tires are underinated. Conversely, overinating

the tires to reduce rolling resistance isn’t really worth

Note that the power required

actually increases with the cube

of the speed, because speed is

present in power equation as well

as speed squared in the equation

for wind resistance. Speed really

does kill… efficiency, anyway.

JAN/FEB 2018 25

Example: a 2,175 kg vehicle with 2.34 m² of frontal

area and a Cd of 0.24 traveling at 110 kph on a road with

a 5% grade:

Fr = 2,175 * 9.81 * 0.015 = 320.0 N

Fw = 0.5 * (110 / 3.6)² * 1.2 * 0.24 * 2.34 = 314.6 N

Fs = 2,175 * 9.81 * sin(2.86°) = 1,064.6 N

P = (320.0 + 314.6 + 1064.6) * (110 / 3.6) = 51,920 W

And if the road is at? Now the power required is

19,390 W. Slope is no joke!

Weight

Weight also has a direct impact on the amount of energy

it takes to change speed. It probably goes without say-

ing, but the heavier the vehicle the more energy will be

expended to increase its speed. e relevant formula for

determining such is:

K = 0.5 * m * v²

Where K is energy (in Joules, J, aka W-s), m is mass

(aka weight, in kg) and v is velocity (aka speed, in m/s).

For example, to increase the speed of a 2,000 kg vehicle

by 72 kph requires 400 kJ (or 0.111 kWh). at might not

seem like much, but it can add up surprisingly quickly

rst change percentage into decimal format (e.g., 10% =

0.1) then take the arctangent of the resulting number to

get the slope in degrees (e.g., arctan(0.1) = 5.71°).

With the slope in degrees the following equation can be

used to nd the drag force from a change in elevation:

Fs = m * 9.81 m/s² * sin(Θ)

Where Fs is the drag force from a slope in N (Fs is a

positive number if going up the slope and a negative num-

ber if going down), m is the vehicle mass in kg, 9.81 m/s² is

the gravitational acceleration of Earth, and Θ is the slope

in degrees. For example, a 2,000 kg vehicle going up a 10%

grade experiences a drag force of 1,952 N (or 199 kg-f).

Putting all the above together in another example

should help solidify an understanding of the concepts:

THE TECH

Photo courtesy of Jakob Härter - CC BY-SA 2.0

Photo courtesy of Norsk Elbilforening - CC BY 2.0

in stop-and-go trac, and the ability of EVs to recap-

ture some of this energy via regenerative braking is one

reason why they deliver superior “fuel” eciency in city

driving compared to their ICE counterparts.

Regen

While regenerative braking can recapture some of every

positive change in speed, keep in mind that energy must

be fully converted twice when regen is used, so it incurs

twice the losses.

Using the above equation for kinetic energy for a 1,000

kg vehicle decelerating from a speed of 100 kph gives a

result of 384 kW-s (kilowatt-seconds). Divide by 3,600 to

convert seconds to hours and that gives us a rather paltry

0.11 kWh of recovered energy - assuming 100% eciency.

Multiply 0.11 kWh by the price for electricity ($0.11

per kWh) and the resulting savings is $0.0121. Still, you

can’t make gasoline by braking in an ICE vehicle so any

energy recaptured by regen is better than nothing.

It bears mentioning that along with regen, the two

other reasons EVs excel in city driving are that they

don’t need to idle their motor while stopped, nor do

they need to use energy over and above what is required

to deliver good acceleration performance. In the bad

old days of carburetors and the rst port fuel injection

systems, there was a pump that literally sprayed a dollop

of fuel every time the accelerator pedal was pressed, just

to make sure the engine didn’t run too lean and stumble

(of course, the engine could also stumble from running

too rich).

Climate control

e nal factor that can aect energy consumption -

sometimes dramatically so - is cooling or heating the

cabin. Many rst-generation EVs used a conventional

automotive AC system, except that the compressor was

driven by its own electric motor, rather than by a belt to

the traction motor. Using a dedicated motor is a more

costly solution, but it is far superior, as the compressor

always runs at its optimal speed, allowing it to be more

ecient, and cooling isn’t lost every time the vehicle is

stopped, since the traction motor doesn’t idle in an EV.

One huge disadvantage of the conventional automo-

tive AC system is that it only pumps heat in one direc-

tion; there was no need for it to operate bidirectionally

(i.e., as what is commonly thought of as a “heat pump”)

because the ICE is a proigate producer of waste heat

which comes at no additional burden to the engine or fuel

economy. In contrast, the eciency of the EV inverter

and motor combination - the only potential sources of

waste heat of any magnitude - is typically in the high 90s

and the losses directly scale with power output, so you

might get a reasonable amount of waste heat climbing

hills all day, but very little driving the speed limit on any

limited-access highway in the US.

So, heating the cabin in an EV requires an additional

source of heat. Many early designs used resistance heat-

ing, as it is cheap, simple and 100% ecient at converting

electricity into heat. at last spec sounds impressive,

except that the typical compressor-type heat pump can

move around 2 - 4 W of heat for every 1 W of electrical

input power; the so-called “Coecient of Performance”

in refrigeration/HVAC parlance. is is also why switch-

ing from almost any kind of furnace to a heat pump tends

to save quite a bit of money heating a home. Another

bonus of the heat pump operating as a heater (rather than

as an AC) is that waste heat produced by the compressor

is useful, so the COP tends to be 1 higher in heating mode

compared to cooling.

For a more concrete example, the average vehicle needs

somewhere in the range of 4-8 kW of heating/cooling ca-

pacity, depending on interior volume, exposed glass area,

insulation R value, outside temperature, etc. If heating is

via electrical resistance then that will be a direct 4-8 kW

of additional drain on the battery, whereas if it is supplied

by a modern heat pump system with a COP of 4.0 in heat-

ing mode, then only 1-2 kW will be drawn (with 1.33-2.67

kW drawn in cooling mode, as COP will then be 3.0).

Using the previously worked example for vehicle power

demand, 19.4 kW was required to travel at 110 kph on

the at, so an additional draw of 2 kW for climate control

would be equivalent to increasing the speed by nearly 6

kph or decreasing the range by 10%. Bumping the draw

up to 8 kW for an electric resistance heater would be

equivalent to increasing speed to 130 kph or cutting range

by 40%!

THE TECH

26

You can’t make gasoline by

braking in an ICE vehicle so any

energy recaptured by regen is

better than nothing.

Photo courtesy of FotoSleuth - CC BY 2.0

Efficiency

Last to be considered is the

question of how changes in the

eciency of some of the major

drivetrain components aect en-

ergy consumption. e inverter

seems to receive a lot of the focus

here, but there really isn’t much

room for improvement - 98% is

already achievable using state-

of-the-art 600 V IGBTs, and to

get to 99%, say, would require

cutting losses in half…good luck

with that. e traction motor

is a juicier target as it typically

operates with an eciency in

the 80-90% range, but improv-

ing motor eciency invariably

results in a bigger (and costlier)

motor. Still, higher eciency in

both these components can have

positive eects in other areas,

such as reduced cooling com-

plexity/cost and, of course, even

a small eciency boost can add

up to signicant energy savings

over the life of the EV.

Using the same example as

above, if the average eciency

of the motor is improved from

90% to 95% (easy to achieve for

an industrial motor operating at

a xed load; a rather more heroic

achievement for a traction motor

in an EV), then the power would

drop from 21.56 kW to 20.42 kW

(assuming 19.4 kW required at

100% eciency), which works

out to a savings of around $0.125

per hour if energy costs $0.11

per kWh. Guesstimating a 5,000

hour operational life for the EV

(e.g., 300,000 km at an average

speed of 60 kph), that works out

to a lifetime savings of $625,

minus whatever it cost to achieve

the eciency improvement (a

gure which may very well ex-

ceed the savings).

PERMANENT

MAGNET MACHINE

28

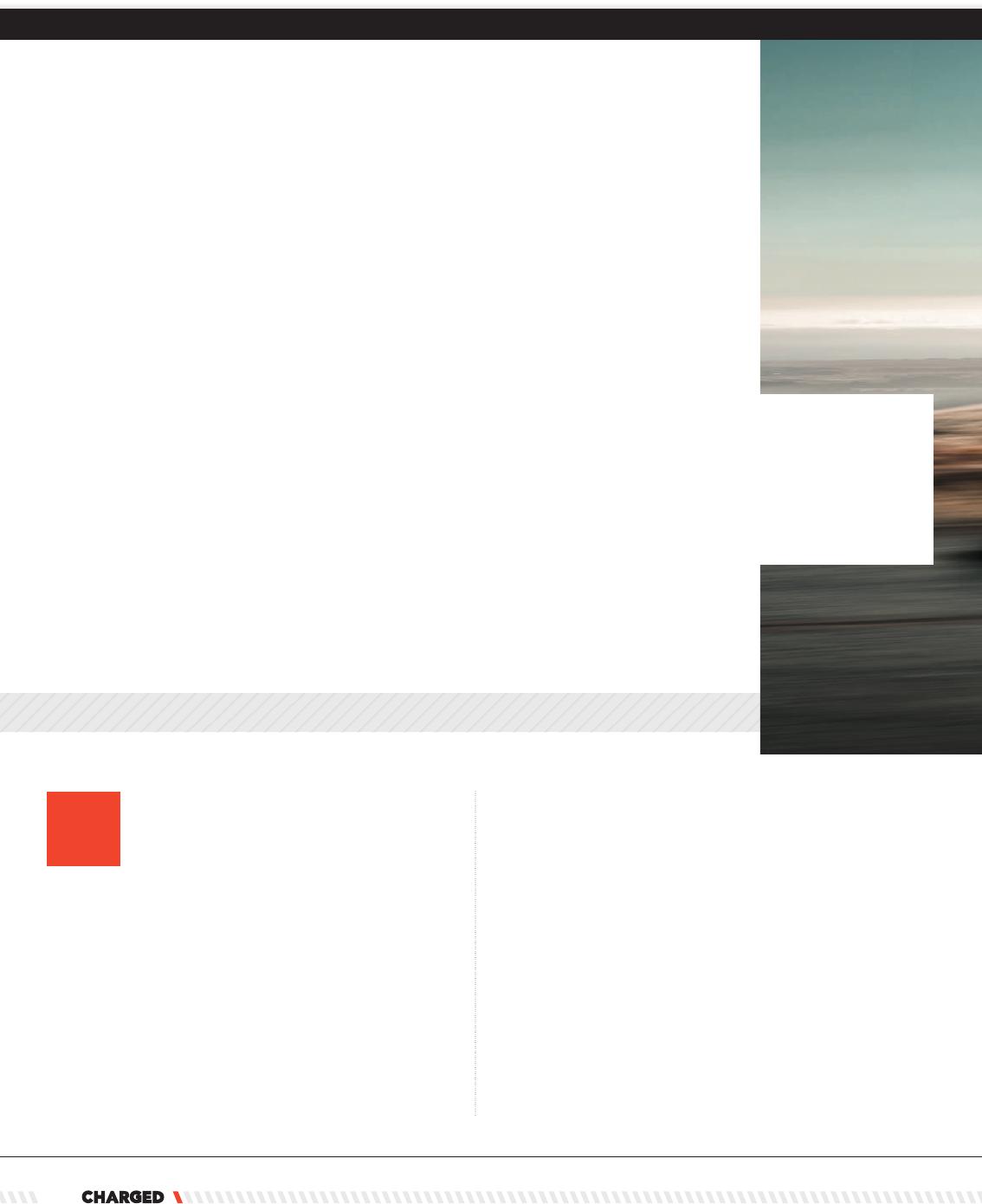

ost mainstream EVs from major automak-

ers have used some form of permanent

magnet traction motor technology, with

two high-prole exceptions: Tesla’s Model

S and Model X both use induction motor technology.

Internet engineering forums are full of compelling

arguments for using both technologies in vehicles,

as well as loads of speculation on what drove Tesla to

favor induction machines from day one.

e best explanation I’ve read is one based on

historical factors. By many accounts, the reason Tesla

started developing an induction motor in the rst place

is because it inherited the design from AC Propulsion.

e induction motor used in the Roadster actually

had roots going all the way back to GM’s EV1 motor,

which was designed by Alan Cocconi. Cocconi based

it on existing AC induction motor specs. Tesla ini-

tially licensed the design from Cocconi’s company, AC

Propulsion. However, Marc Tarpenning later said that

Tesla had completely redesigned its induction machine

“a year before we were in production…long before we

were even into the engineering prototypes.” A lot has

changed since those early days in terms of available

R&D technology and material costs.

In any case, Tesla’s exclusive use of induction ma-

chines has been intriguing to motor experts and EV te-

chies. So, it was particularly interesting in August 2017

when Model 3’s EPA certication application revealed

a big change in the powertrain - the document states

that Model 3 uses a 3-phase permanent magnet motor.

Tesla rarely oers ocial comment on technology

decisions, so it can be hard to discern the exact engi-

M

By Christian Ruoff

FOR MODEL 3

TESLA’S TOP MOTOR ENGINEER

TALKS ABOUT DESIGNING A

THE TECH

JAN/FEB 2018 29

jor automakers, Laskaris wasn’t at liberty to tell us

all about the specic quantitative analysis that led to

choosing a permanent magnet motor. However, he did

oer some interesting insights into the engineering

processes the company employed in the analysis.

e following is a transcript of our on-stage conver-

sation, edited slightly for clarity.

Konstantinos Laskaris: It’s well known that

permanent magnet machines have the benefit of

pre-excitation from the magnets, and therefore

you have some efficiency benefit for that. Induc-

tion machines have perfect flux regulation and

therefore you can optimize your efficiency. Both

make sense for variable-speed drive single-gear

transmission as the drive units of the cars.

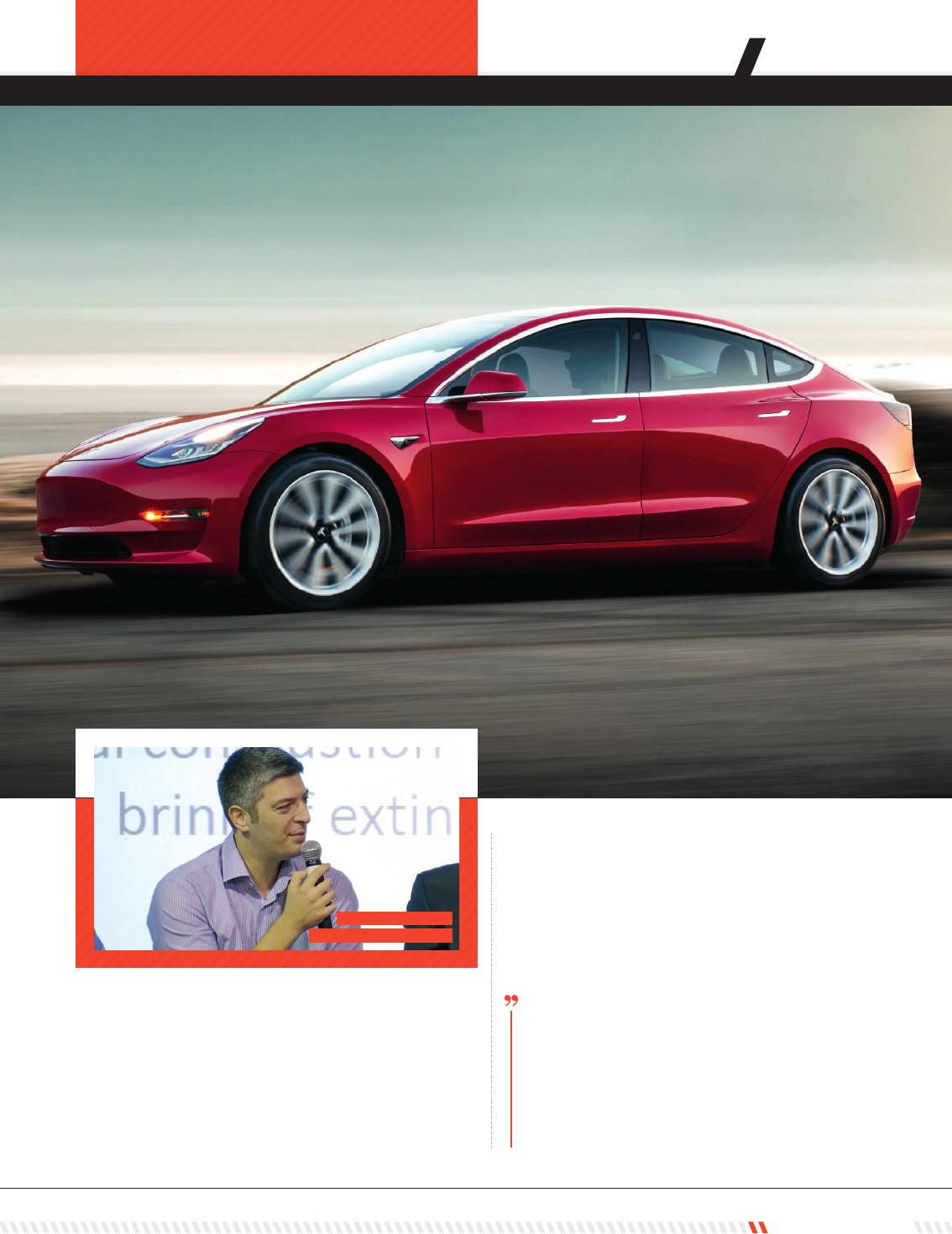

neering thought process. Luckily, I recently moderated

a keynote panel discussion of EV tech experts at the

Coil Winding, Insulation & Electrical Manufacturing

Exhibition (CWIEME) in Chicago. e panel included

Konstantinos Laskaris, Tesla’s Chief Motor Designer,

so I had the chance to pry a few more details from the

world-class motor engineer.

As usual when interviewing engineers from ma-

Konstantinos Laskaris,

Tesla’s Chief Motor Designer

30

So, as you know, our Model 3 has a permanent

magnet machine now. This is because for the

specification of the performance and efficiency,

the permanent magnet machine better solved our

cost minimization function, and it was optimal for

the range and performance target.

Quantitatively, the difference is what drives the

future of the machine, and it’s a tradeoff between

motor cost, range and battery cost that is de-

termining which technology will be used in the

future.

Laskaris later added: When you have a range tar-

get [for example], you can achieve it with battery

size and with efficiency, so it’s in combination.

When your equilibrium of cost changes, then it

directly affects your motor design, so you justify

efficiency in a more expensive battery. Your opti-

mization is going to converge on a different motor,

maybe a different motor technology. And that’s

very interesting.

If you combine these comments with those made

by Laskaris during our 2016 on-stage interview at the

CWIEME event in Berlin, you begin to see a clearer

picture of the sophisticated process Tesla uses to

evaluate different motor designs and optimize them

for the specific desired parameters of each vehicle.

Laskaris: Understanding exactly what you want

a motor to do is the number-one thing for opti-

mizing. You need to know the exact constraints

- precisely what you’re optimizing for. Once you

know that, you can use advanced computer models

to evaluate everything with the same objectives.

This gives you a panoramic view of how each mo-

tor technology will perform. Then you go and pick

the best.

With vehicle design, in general, there is always a

blending of desires and limitations. These param-

eters are related to performance, energy consump-

tion, body design, quality, and costs. All of these

metrics are competing with each other in a way.

Ideally, you want them to coexist, but given cost

constraints, there need to be some compromises.

The electric car has additional challenges in that

battery energy utilization is a very important con-

sideration.

This is the beauty of optimization. You can pick

among all the options to get the best motor for the

constraints. If we model everything properly, you

can find the motor with the high-performance

0-60 constraint and the best possible highway ef-

ficiency.

For the specification of the

performance and efficiency,

the permanent magnet

machine better solved our cost

minimization function, and it

was optimal for the range and

performance target.

JAN/FEB 2018 31

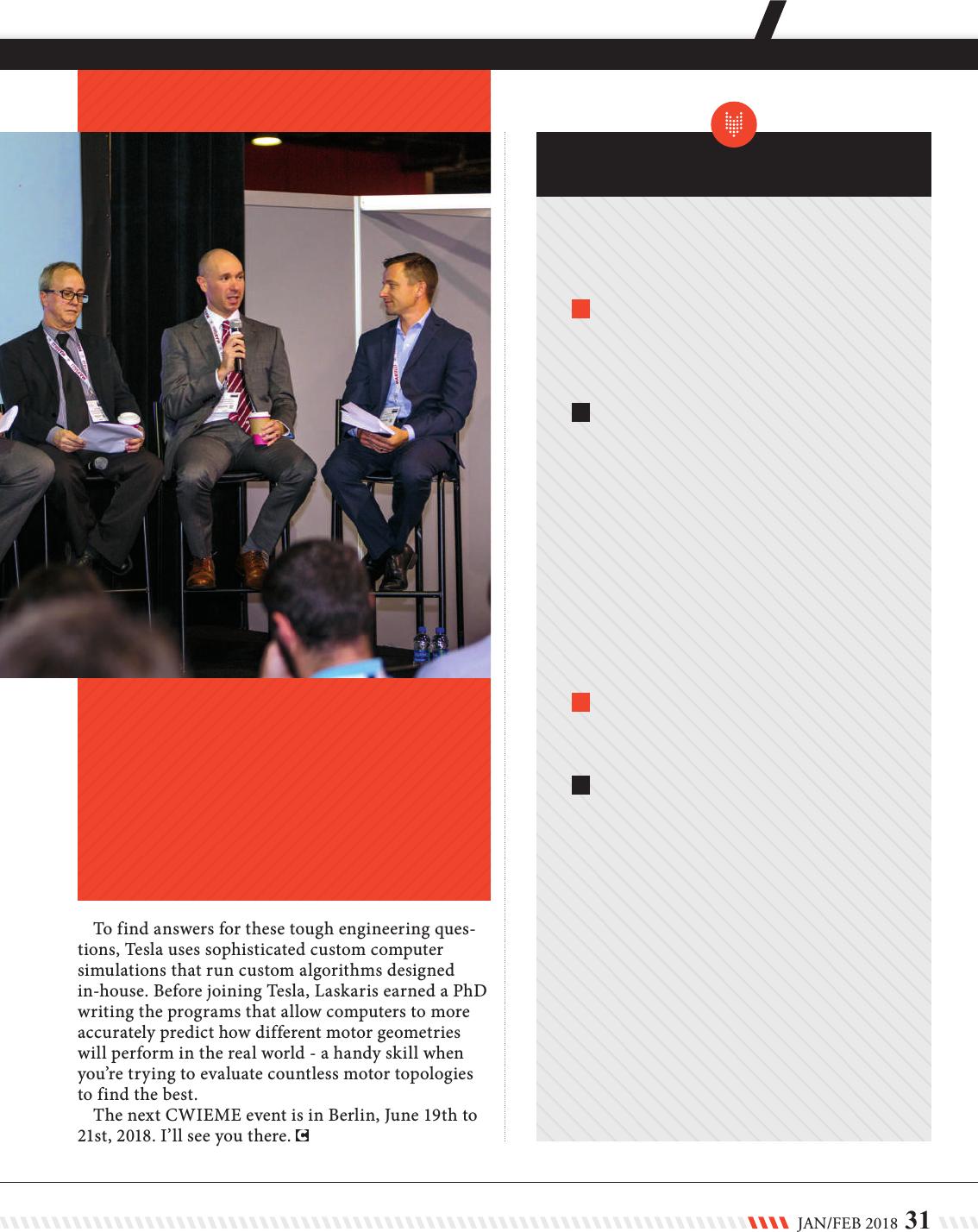

To find answers for these tough engineering ques-

tions, Tesla uses sophisticated custom computer

simulations that run custom algorithms designed

in-house. Before joining Tesla, Laskaris earned a PhD

writing the programs that allow computers to more

accurately predict how different motor geometries

will perform in the real world - a handy skill when

you’re trying to evaluate countless motor topologies

to find the best.

The next CWIEME event is in Berlin, June 19th to

21st, 2018. I’ll see you there.

During our Chicago panel discussion, Laskaris also

made a few other comments that our motor enthu-

siast readers might nd interesting.

Q

What are the most critical motor design

parameters that EV motor designers care about?

High torque density, high power density, high

speed, size, etc?

A

Laskaris: Power density is a very important

parameter. For electric vehicles you have the gear

that can transform the power density into torque

density. Therefore you can take advantage of a

power-dense machine being compact, and can create

the requested tractive eort to the car. Also, power

density is minimizing the materials cost. So when the

specications allow for a power density increase it

should always be taken. I think that is a rule for motor

design. You can build power density through torque

density and through speed, and you should not be

neglecting one thing for the other when you’re

designing a machine for particular specications.

Q

How is stator and rotor cooling technology

impacting electric machine design - for example,

slot cooling, water jackets, direct coil cooling, etc?

A

Laskaris: The rotor thermals and the stator

thermals are aecting the design of the motor in

dierent operating conditions. Like when you’re at

dierent torque speed points, you’re constraining

the rotor thermals and the stator thermals,

especially when you’re operating in eld weakening

in variable-speed drive single-gear transmissions.

This means that cooling technologies can have

dierent gravity according to what you are designing

for, and dierent eectiveness. Overall, cooling

technology allows you to achieve higher continuous

capability in the machine. And that’s very important

because that drives the size of the machine as well.

So you can cost-eectively design machines that do

the same thing if you can drive them at higher

continuous points.

THE TECH

The EV technology expert panelists at the CWIEME Chicago

event included, from left to right,

• Jaydip Das - Carpenter Technology Corporation,

• J. Rhett Mayor - DHX Machines,

• Konstantinos Laskaris - Tesla,

• Peter B. Littlewood - Argonne National Laboratory,

• Tom Prucha - Protean Electric,

• Matthew Doude - Mississippi State University, and

• Christian Ruoff - Charged Electric Vehicles Magazine.

A broader discussion

By Paul Beck

IONIC

MATERIALS

IN SOLID-STATE BATTERIES

BY FOCUSING ON

EMERGES AS A LEADER

POLYMER

SCIENCE

32

Photo courtesy of Ionic Materials

THE TECH

ike Zimmerman, CEO and founder of Ionic

Materials, has this to say about his company:

“Ionic will play a major role in the solution

to the world’s energy problems.”

at’s a pretty bold statement. But then again, Mike

Zimmerman is a pretty bold man. An experienced

polymer scientist, Zimmerman has worked on a number

of ground-breaking technologies, from the rst ber-

to-the-home system in electronics to the rst plastic

package for semiconductors. He started and sold a

successful materials science company called Quantum

Leap Packaging, and has spent the last 25 years teaching

materials science at Tus University.

But all that was only the prelude to Ionic Materials.

“For some reason, ve years ago I started thinking

about batteries,” Zimmerman says. “I wasn’t a battery

person, but I started looking at the materials of a bat-

tery. I saw that a lot of the improvements were being

made on the anodes and cathodes, and I noticed that the

electrolyte was a real limiting factor.”

With that one serendipitous observation, Zimmerman

had begun his journey to help solve the world’s energy

problems.

M

JAN/FEB 2018 33

34

oxide. Although this substance can transfer ions, it suers

from two major drawbacks: it’s only conductive at high

temperatures, and it’s not compatible with high voltages.

“So I said, being a polymers person, it would be very

benecial if somebody could develop a polymer that

could be extruded, and used plastics processing technol-

ogy that could actually function appropriately at room

temperature. So I started working on a polymer electro-

lyte that could be as functional as a liquid electrolyte but

would solve a lot of the problems of a liquid electrolyte,

mostly safety and energy density.”

The solid solution

rough his eorts, Zimmerman managed to develop

a solid polymer which addressed the limitations of

polyethylene oxide - and opened the door to a better

type of battery.

“What I did as a polymer scientist was to come up

with a material which has a completely dierent conduc-

tion mechanism,” Zimmerman explains. “It doesn’t re-

The trouble with liquid electrolytes

“Since about 1990, the major rechargeable battery has

been a lithium-ion battery,” Zimmerman told Charged.

“And it had a liquid electrolyte. And I said to myself, you

probably couldn’t put together three worse materials:

reactive anode, cathode, and this very ammable liquid

electrolyte.”

By now, the hazards of liquid-electrolyte lithium-

ion batteries are pretty well known to the public. Even

though they’re ubiquitous in all sorts of devices, from

personal electronics to EVs, they do occasionally short-

circuit and catch re. In 2016, for example, smartphone

manufacturer Samsung was forced to recall 2.5 million

Galaxy Note 7 phones aer reports of res resulting

from manufacturing defects. A quick YouTube search

will also reveal video aer video of what happens if lith-

ium-ion batteries are punctured (spoiler alert: smoke,

smoldering, ames and the occasional rapid release of

gases - i.e. explosion).

One approach to this problem is to swap the am-

mable liquid electrolyte for something more durable: a

solid. And although this is the approach Zimmerman

took, he was not the rst to try it.

“ere’s been two classes of solids, ceramics and

glasses,” he explains. “And they all have their challenges.

One of the big challenges with both is to make them

thin and big. Ceramics are very brittle, so it’s hard to

scale them up. And you can imagine even putting glass

in an electrolyte is a dicult challenge.”

Zimmerman, with his background in polymer sci-

ence, saw the potential advantages of developing a solid

polymer electrolyte. Before he began his work, there was

only one such electrolyte: a polymer called polyethylene

It would be very beneficial if

somebody could develop a

polymer that could be extruded

and used plastics processing

technology that could actually

function appropriately at room

temperature.

Photos courtesy of Ionic Materials

JAN/FEB 2018 35

is that we’re enabling electrodes made of lithium metal,

which has much higher energy density.” One of the

major challenges with lithium metal electrodes comes in

the form of dendrites, ngerlike projections of metal that

build up from one electrode, harming performance and

eventually creating a short circuit. Replacing liquid elec-

trolytes with an aordable and functioning solid creates

a physical barrier that will prevent dendrite formation.

A third benet of Ionic Materials’ approach is that it

has the potential to lower the cost of batteries. For one

thing, there are some cost savings that can be attained by

using plastics manufacturing and eliminating the liquid

electrolyte. For another, the new polymer can enable

certain alternatives to lithium-ion chemistries, such as

rechargeable alkaline, which uses cheaper electrodes

than lithium-based batteries do.

All of this has the potential to make a big impact in the

world of EVs, as Zimmerman points out.

“What’s going on is the automobile industry is really

in a push to turn cars from internal combustion to bat-

teries,” he says. “And in order to do that, they’re work-

ing on several things: range, cost, and safety. And our

polymer has a great chance to solve the range, the cost,

and the safety issues with traditional lithium-ion.”

quire movement of the chains. e conductivity at room

temperature is equivalent to that of a liquid electrolyte

with a separator. And the polymer is processable like in

roll-to-roll, so it’s highly manufacturable. at’s what

separates us from everybody else.”

In a conventional lithium-ion battery, two electrodes

- the anode and cathode - are on either side of a separa-

tor, which prevents a short circuit while allowing ion

transfer. e liquid electrolyte, which conducts the ions,

surrounds each electrode.

Zimmerman’s new material allows for a unique bat-

tery architecture. “We’re replacing both the separator

and liquid electrolyte with polymer,” he says. “So the

ionic polymer does two functions: it’s electrically insula-

tive, so it acts as the separator, and it’s ionically conduc-

tive, and acts as the electrolyte.”

is approach creates a completely solid-state lithium-

ion battery, which unlocks a number of benets. Chief

among them: safety.

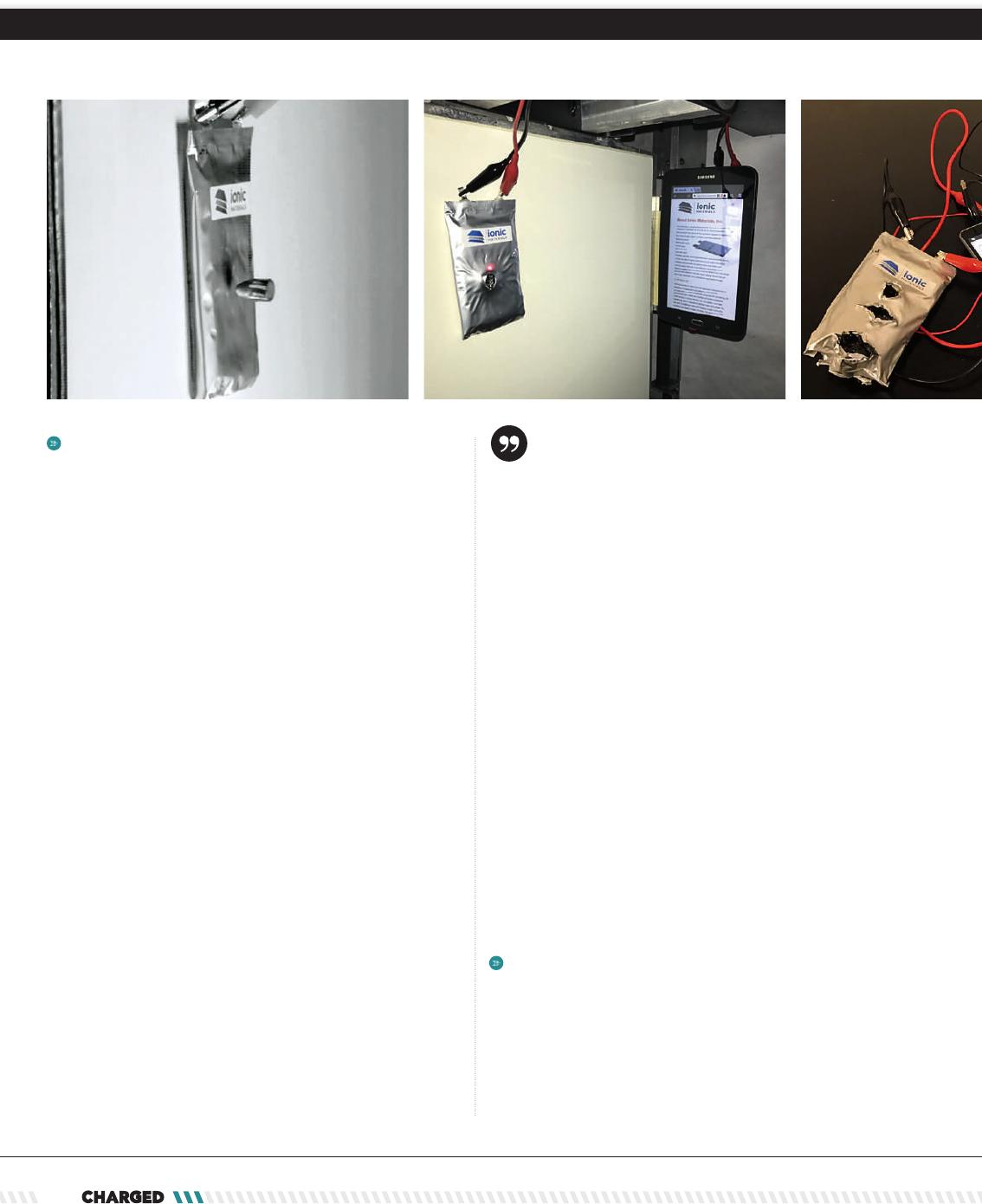

“You can shoot bullets through a battery made with

our material and it won’t explode, it won’t burn, and it

still works aerwards,” claims Zimmerman. But don’t

take his word for it - you can actually go to the Ionic

Materials website and watch a video of exactly that. e

technology was also featured on a recent Nova docu-

mentary, Search for the Super Battery, in which you can

see Zimmerman’s battery get cut, stabbed, and burned

without giving o so much as a single spark (and while

remaining completely functional).

But the advantages don’t end there, according to Zim-

merman.

“People are trying to go to higher energy density an-

odes and cathodes,” he says. “And another major benet

You can shoot bullets through

a battery made with our

material and it won’t explode,

it won’t burn, and it still works

afterwards.

THE TECH

36